While excellent newsletters on specific themes within public policy already exist, this thought letter is about frameworks, mental models, and key ideas that will hopefully help you think about any public policy problem in imaginative ways. If this post was forwarded to you and you liked it, consider subscribing. It’s free. If you enjoy what’s written here, you will also like our book, Missing in Action: Why You Should Care About Public Policy. Global Policy Watch: Tariff Karun Kya UskiInsights on global issues relevant to India— RSJSample these news reports from the past week:

For the sake of my sanity, I have stopped tracking tariff news coming out of the Trump administration any more. It is difficult to keep track of this stuff - new rates, new commodities, new countries, new threats, new deals and rollbacks. For reasons that I am yet to comprehend, Trump thinks tariffs are the solution to all the current economic and social woes of the US. Trade imbalance, weak manufacturing base, fiscal deficit, income inequality, immigration, crime, drug and fentanyl inflow, price of eggs - everything can be solved once Trump gets global trade partners to stop ‘fooling’ America. It is a solution so deceptively clever and simple that no one had thought of it until Trump came along. Genius does what it must. Or something like that is at play, I guess. Anyway, the reason no one has used this tariff playbook like this before is quite simple. It is wrong. What I will try to do in this post is explain in simple terms why this is wrong and what might be the eventual outcome of pursuing this line of tariff imposition. Before going there, it will be helpful to understand the case for tariffs made by those who support Trump. Is there a reason why the long-held orthodoxy about tariffs being a net negative in almost all cases is being challenged today? Those favouring tariffs start with two key assumptions: one, there should be no trade imbalance between countries over time and two, domestic industrial policy and trade policy should be seen together when analysing trade imbalances. It is useful to understand these assumptions better. A core argument here is that for several decades now, several advanced economies, notably the US, have had a persistent trade deficit which hasn’t corrected itself through price adjustment as it should have. What this means is that over time, the self-regulating mechanism should have kicked in; that is, the Dollar should have devalued itself to make exports more attractive and imports costly and bridge the trade deficit. The reason this hasn’t happened is that countries like China have used their domestic industrial policy—production subsidies, easy credit to the industry, repressed labour costs, restrictions on labour mobility in tandem with trade policy that is supported by tariffs, import controls and an undervalued currency—to keep their manufacturing competitiveness artificially high. The domestic industrial policy therefore acts as a proxy to trade policy and doesn’t allow the comparative advantage between the US and China to play out as written in textbooks. The numerous distortions engineered through the industrial policy effectively subsidise the Chinese manufacturers by transferring the wealth from Chinese households. The Chinese households remain weak on consumption and the Chinese manufacturers have to find external markets to dump their goods. This, they argue, was what China did in the decade after joining the WTO. And after its failed attempt at getting domestic consumption going about 7-8 years ago (way too disruptive for them), this is what it is doing once again with its massive investment in green and decarbonisation infrastructure that it is now raring to export. It is now referred to as the second China shock for the global economy. In effect, the US will continue to pay the price of a distorted Chinese industrial policy that suppresses domestic demand, subsidises manufacturing and externalises the excess capacity to keep the trade deficit high. This has hollowed out American manufacturing while its consumers overconsume. The problem isn’t just limited to this. Because capital flow into the US is free from controls, the trade surplus of China has meant Chinese capital has flown into America buying domestic assets, mostly bonds and stocks. This excess capital has meant the domestic savings rate in the US is unnaturally low, further reducing aggregate household savings and rewarding consumption. Logically, this systematic hollowing out of US industrial capabilities should have shown up in rising unemployment rates. But that isn’t the case. That is explained away by the successive US governments expanding the fiscal deficit to support creation of demand and keeping interest rate low which further increases household debt. The answer to this persistent trade imbalance, the root cause of all evils, engineered by a distorted industrial policy of China is therefore simple. First, a blanket tariff on all goods from China and, in fact, from any country that imposes high tariffs on American goods (the reciprocal tariffs of Trump). Or, eventually create a coalition of US partners who will take similar tariff measures against all trade distortionists like China in tandem. Second, bring in capital controls to prevent China from exporting its savings to buy up US assets. This will take away the incentive of China to externalise its excess capacity and force it to balance its economy in favour of domestic consumption, however painful it might be. This should be the primary desired outcome of trade policy when dealing with China. Most of these arguments don’t have a solid framework supporting them or even evidence that is broad-based. But it is simplistic enough to explain to people how they are being fooled by China (or even Mexico and the EU) and empirical enough to explain the recent history of how global economics has played out. And like it has always happened in the past, no sooner than a political idea, however flawed in its economics, starts gaining currency, you have ”economists of the moment“ arrive, justifying them using cherry-picked data and broad assumptions. A few years back we had the muddled modern monetary theory (MMT) that was used to justify any amount of fiscal deficit because a sovereign can simply print money to pay off the interest. I haven’t seen them around since inflation beat Biden and the Democrats. This is what has happened now with the economics of trade policy in the past couple of months, with a set of Trump-leaning experts trying to rewrite international economics with the apparent logic I have laid out above. Why is this wrong? Four reasons. First, reducing the balance of trade isn’t always positive for a nation’s gross domestic output. We go back to the simple definition of GDP: GDP = consumption + investment + government spending + net exports Net exports = exports - imports and represents the balance of trade. So GDP can be represented as: GDP = consumption + investment + government spending + exports - imports The imports are subtracted because some part of consumption, investment or government purchases would have been imported and that should be subtracted from the total to represent the true picture of total domestic product. Now a superficial reading of the above equation will suggest that reducing net imports will increase GDP. The general belief in the Trump camp is that an increasing trade deficit means the economy is importing things that could have otherwise been produced domestically. The thinking here is that if you reduce imports by some amount, then an equal amount of that demand will be taken up by the domestic products, thereby keeping the total consumption and investment spending constant. Thus, reducing imports will increase the net exports without changing any other variable in the GDP equation. The GDP will therefore rise by the amount of imports reduced. If only life were that simple. Trade balance has a complex interplay with the other three variables of consumption, investments and government purchases. Reduction in imports doesn’t easily redirect that amount of demand in domestic production. because domestic production requires that import to begin with. It is not easy to start producing that import without redirecting some of domestic capacity towards it at possibly higher prices. In an economy that is close to full employment, it is impossible to redirect that labour too. The reason for why import is falling is important to know before deciding if it will help in GDP growth. If you remember, during peak COVID-19, we actually had a quarter where our trade balance turned positive. That was not because all those imports went down and we started producing goods locally. Rather, sadly, it was because domestic demand had collapsed, and we had GDP shrinking by over 10 per cent. In fact, across most countries, GDP falls when the trade deficit shrinks. This can be confirmed statistically with certainty for the US economy. Among most industrial economies, the trade deficit is countercyclical - it is high during a boom and falls during a downturn. Second, the other vital equation to keep in mind while discussing trade is this. Exports - Imports = Savings - Investments Or, Balance of trade = Balance of payment A tariff on imports will make it more expensive, reduce balance of trade and therefore improve the balance of payment. This will mean an appreciation of the dollar in the forex market, as seen in the past few months, as the US tariff policy under Trump has started to become real. Dollar appreciation will mean that US exports will get more expensive for the rest of the world while imports will get cheaper. In a short time, this will offset whatever positive impact the tariff had on the trade balance. This is how this script has played out in umpteen cases. We will be back to square one with a worse outcome on GDP because the distortion of tariffs will mean that the US will produce those goods that were previously imported at higher cost by directing resources from other parts of the economy. Eventually, this will impact exports, and they will fall too. Despite empirical and economic evidence of this, for some reason, the Trump camp believes they will be able to manage the currency appreciation issue by implementing an even greater policy mistake - controlling foreign capital flows into the US. And that brings us to the next reason. Third, like reducing trade balances won’t necessarily impact GDP growth, reducing the balance of payments won’t work either. Countries can trade in either goods and services or financial assets. The current account balance is the difference between exports and imports of goods and services, while the financial account balance is the net trade that happens on things like stocks and bonds. For every single transaction of a product or service between two countries, there is a corresponding financial transaction that happens to square off that trade. This leads to the other critical equation: Financial account balance = current account balance It is tempting to think that by placing restrictions on foreign capital inflow that buys up US assets, one can increase the financial account balance and thereby improve the current account. But then this is not a mere mathematical equation that will work this way. Once again the empirical evidence would suggest such control on capital inflows don’t necessarily lead to GDP growth. In fact, such measures, say if the US were to tax capital flowing in to keep the Dollar weak, will lead to significant disruptions in the global financial market and a possible move away from the Dollar as a reserve currency before one can figure out if it has helped the US economy. The odds are low it will. Finally, the way global supply chains work today, it is impossible to imagine that U.S. manufacturers will make everything onshore. It will have to order all kinds of intermediate goods from abroad to make the products that it wishes to stop importing. These intermediate goods will be costly with the tariffs thereby increasing the cost of US manufacturing. Businesses are bigger consumers at the aggregate level than households, and about 64 per cent of US imports are intermediate products that are meant for manufacturers. These are inputs into the production of goods for domestic consumption or exports. This impacts the competitiveness of US exports and raises prices for domestic consumers. A bad outcome overall. So, where do we go from here? I believe that Trump will keep imposing new tariffs and, in parallel, signing new ‘deals’ with countries to show his tariff strategy is working. Most of these deals will likely be the usual bilateral business between the two countries, in new, attractive packaging. Some tariffs will stick like that on China, the EU and on some specific materials like steel and aluminium. Others will be too complicated or dynamic for the bureaucracy (whatever remains of it) to keep pace and implement. On the balance, it will be chaotic, and there will be some increase in average tariff across the board. The uncertainty and the tariffs will mean the Dollar will appreciate and negate whatever trade balance benefits the tariffs were supporting. It will eventually be a net negative for the US GDP. Trump will use the tariff revenue increase to justify tax cuts for corporations and households. The tariff revenues will be temporary, but the tax cuts will be permanent. Tariffs will be inflationary for the economy. A higher fiscal deficit with higher inflation. That’s where the U.S. economy will end up. Any plan to control capital flow through taxes and a voluntary move away from the dollar as a reserve currency will have Wall Street up in arms. That’s a bridge too far for most, even in this administration. So, a lot of theatrics and bad policy-making for no real reward. That’s how it will pan out by 2028. Matsyanyaaya: Tilting at WindmillsBig fish eating small fish = Foreign Policy in action— Pranay KotasthaneThe transatlantic alliance is in a bad shape. Is that because it has a word—”trans”—that Trump hates? Whatever the reason, things came to a head at the Munich Security Conference—a top talk shop for strategic affairs concerning the West— where the US Vice President JD Vance castigated a bunch of European countries for failing to uphold freedom and democracy. While the conference's general theme was the Russia-Ukraine war, Vance went on a tangent. He categorically said, “The threat that I worry the most about vis-a-vis Europe is not Russia, it’s not China, it’s not any other external actor. What I worry about is the threat from within. The retreat of Europe from some of its most fundamental values: values shared with the United States of America.” He went on to cite several cases of European countries, from Sweden to Romania and the UK to Germany, trampling over the religious and political freedoms of individuals. In turn, the German Chancellor Olaf Scholz said something that you generally associate with countries like India—we do not accept interference by outsiders in our politics. While Scholz reiterated Europe and Germany’s support for Ukraine, his statement reflected Europe’s predicament far more than its capability. All he could say was that Germany must get its act together to relax the debt regulations, which have hardcoded debt levels into law. Unless changed, Germany will not have the fiscal space to upgrade its security after 2027, he said. It appears that even the war in the vicinity hasn’t moved the Overton Window on this issue in Germany. When questioned about the sagging American commitment towards NATO, he invoked the past: just as Germany and other allies had contributed to the American war in Afghanistan, it was the US' turn to stay true to the NATO charter. So, NATO seems to be at its weakest over the last three decades. Curiously, Russia’s illegal occupation was supposed to have united the West against a common adversary. But three years on, the alliance is a shadow of itself. While the US under Trump wants to wash its hands off the conflict (he spoke to Putin this week about ending the war), Europe hasn’t been able to step up as quickly as it would have liked. Europe’s troubles bring to the fore a core idea about the limits of the fungibility of power. While economic power can be converted to military power, this conversion takes time and purposeful effort. Even a prosperous region cannot rearm quickly. On the other hand, the American position reflects it is increasingly becoming an unexceptional, somewhat normal international actor that speaks the language of reciprocity, multipolarity, and “peace through talks”. Hitherto, the idea of US exceptionalism had caused it to champion the “rules-based world order”, take on expansive global commitments, wage wars far from its shores, and advocate for democratic values. But now it seems the Trump administration itself is convinced that the US is no longer what it once was. Trump’s responses during the visit of the Indian PM were particularly telling. He said:

Even as the US contemplates receding, China’s top diplomat Wang Yi didn’t miss a chance to rub salt into the wounds. He lectured the West on pursuing openness for mutual benefit, respecting international law, and practising equal treatment towards all nation-states. These are signs of a world that has well and truly moved on from its unipolar moment. The US now sees itself as a normal country seeking regular goals. While the rising economic walls are terrible news for all countries, it is not all that bad politically. Countries that previously complained about American influence and overbearing attitude now will have fewer foreign entities to blame. They will have more agency and won’t be able to hide behind America’s overreach. Matsyanyaaya will continue, but the biggest fish seems to have let in some other less big ones in its domain. Meanwhile, other significant developments also took place this week. The Paris AI Action Summit produced a run-of-the-mill statement on AI safety and trust. But even that was rejected by the US and UK, with the American VP saying:

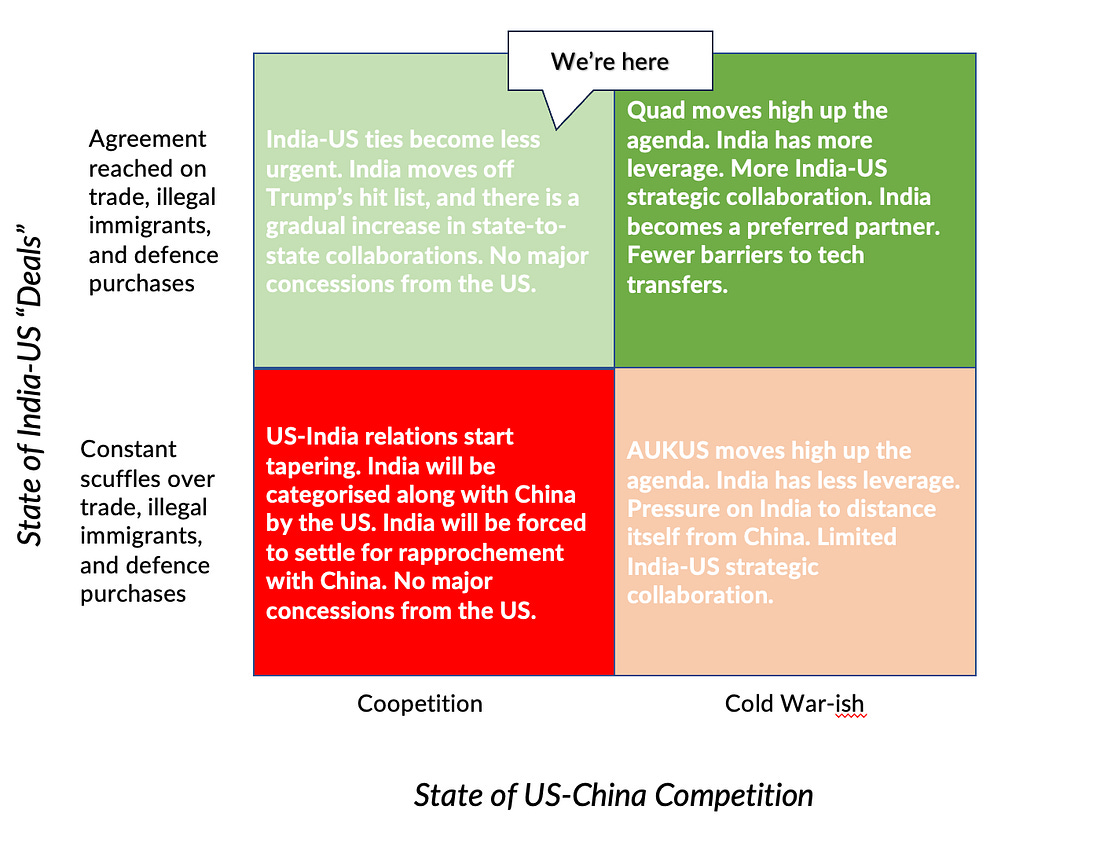

Another case of the US is willingly ceding space to others, particularly China. Amidst all this, the Indian PM had a relatively successful trip to the US. The hot potato issues of trade and illegal immigration, which could have derailed the agenda, were contained rather well, and there was a lot of continuity in technology and defence collaboration. Most importantly, new acronyms were coined: TRUST, COMPACT, BTA, and RDP. Continuing the rich tradition of interpreting the relationship through mathematical identities, this time, we got Make America Great Again [MAGA] + Make India Great Again [MIGA] = MEGA partnership for prosperity. Nevertheless, Trump’s statements on Xi Jinping suggest that, as of now, he wants to step back from a high-tension Cold War with China. Using the framework from the last edition, we are perhaps in quadrant 1. As the joint statement suggests, India played its cards rather well. The announcement to negotiate a mini trade deal later this year helped side-step the question of India-specific tariffs. Specifying a $500 bn bilateral trade target by 2030 was also a terrific outcome. The other prickly issue of illegal migration was diffused with India agreeing to take back deportees without making it a prestige issue. Eventually, illegal migration was mentioned only towards the end of the joint statement. Meanwhile, multilateral cooperation under the Quad appears to have moved down the priority list, given the rethink in the US on its China policy. Meanwhile, tech continued to be the major driver of the relationship. The Initiative for Cooperation on Emerging Technologies (iCET) was renamed Transforming the Relationship Utilizing Strategic Technology (TRUST). There was also a possible reprieve from the AI Diffusion Rules with the statement discussing a roadmap to allow Indian companies access to American AI compute infrastructure provided that measures are implemented to prevent leakages. Finally, India agreed to start the long process of buying some big-ticket items from the US to ‘rebalance’ trade—oil, gas, nuclear reactors, and some defence platforms. All in all, it is a decent outcome for a start. Now, all the eyes should be on how the US-China competition unfolds. HomeWorkReading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

If you liked this post from Anticipating The Unintended, please spread the word. :). If public policy interests you, consider taking up Takshashila’s public policy courses, specially designed for working professionals. Our top 5 editions thus far:

|