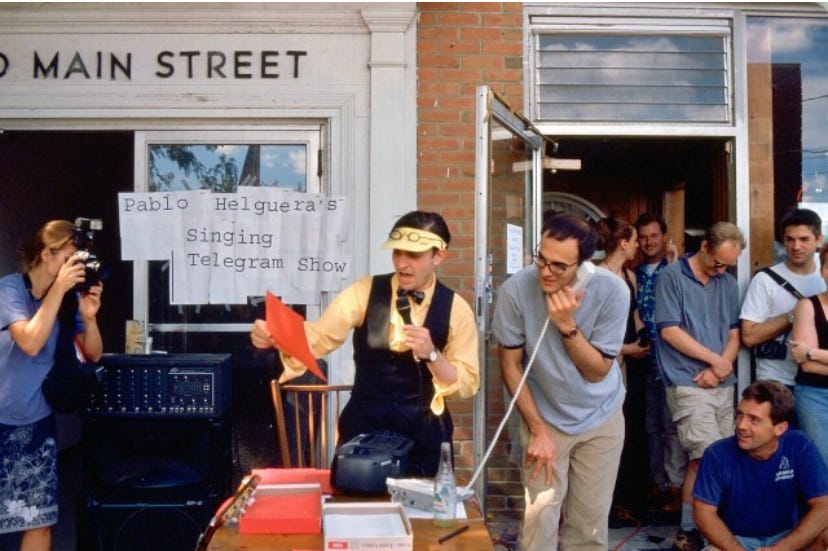

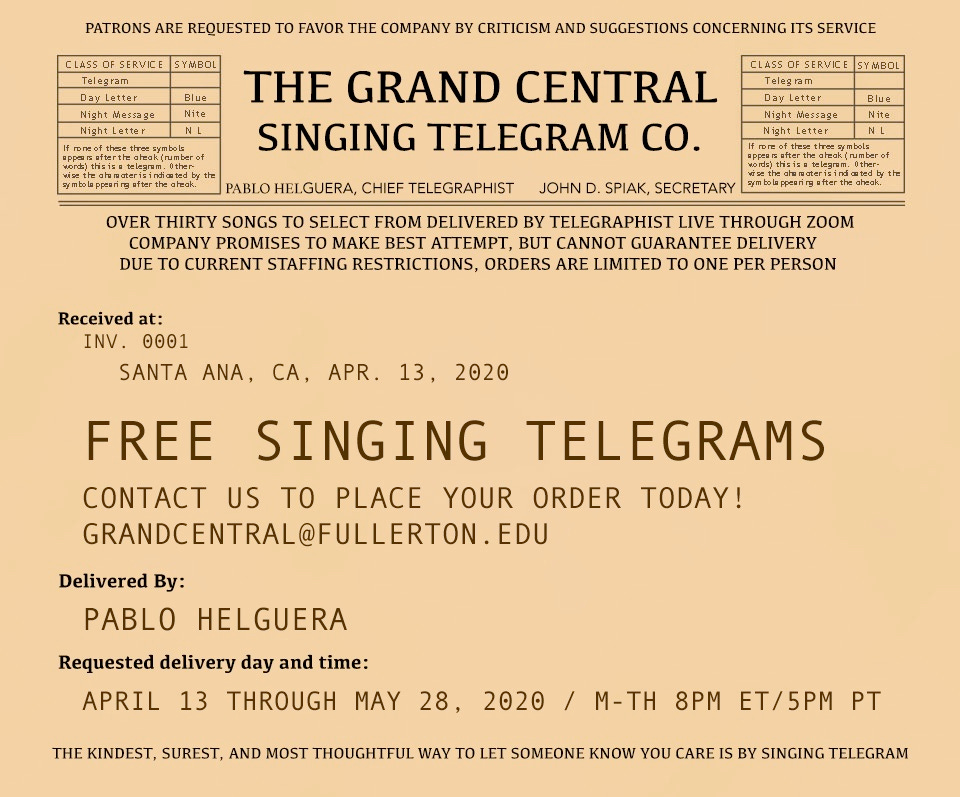

My work has always been, in some way, been about inhabiting different selves. Five years ago, during the COVID pandemic, I found myself taking on the most unlikely of dual roles: that of a telegraphist and opera singer. On March 9th, 2020, New York City had only 20 confirmed cases of COVID-19, and New Rochelle had been designated as a “containment area.” A few days later, we learned of the first confirmed COVID-19 death in the city. At the time, I was still working at MoMA, where we had just launched a major art education initiative in the galleries. My team gathered to discuss their concerns, with some very fearful of contracting the virus from our daily exposure to dozens of daily workshop participants. I did my best to reassure everyone, reviewing the safety measures the museum was implementing. That same day, on my subway ride home, a woman sat next to me. She had a severe cough that made me uneasy. I briefly considered the risk of contagion but somehow dismissed the idea of moving seats, convincing myself it would be an overreaction. All museums closed their doors two days later. Exactly two weeks after that subway encounter—right around the time the city went into lockdown—I began sneezing. I’ve always had spring allergies, so I chalked it up to hay fever. But that night, I realized I had lost my sense of smell, something I’d never experienced before. Still, I refused to believe that I could possibly be infected. After all, I had been fortunate to live a healthy life, never having dealt with a serious illness. That night I woke up in sweat with 102F fever. I went through hell for about a week, trying to quarantine at home from my family. There was no testing available. I had hallucinations and a level of exhaustion that I had never had in my life, perhaps with the exception of a time when I was about 7 years old and caught a virus that kept me in bed for many days after a trip that our family had made to Puebla. I dreamt of the terrifying stone statue of the Commendatore, in Mozart’s opera Don Giovanni, who comes from the grave to drag Don Giovanni to hell. Thankfully, I recovered after a period of extreme exhaustion. The isolation we all went through during that period, as we know led to both a collective and personal reckoning. Collective, with the killing of George Floyd, the way in which the pandemic exposed the deep social and racial inequities in the United States; personal in that we all were forced to reassess the state of our own lives and what, if anything, we should do to improve their course as well as our work-life balance. The Great Resignation brought me to leave my museum life for good and write a performance/post-mortem that addressed that relationship, A Journal of the Year of the Pharmacy. A few days after I recovered, my first impulse was to do a Facebook live where I performed a series of Mexican folk songs. I did it partially to thank the many friends and supporters who had shown concern about my health, and to show them that I was OK. However, in retrospect, I now realize I also did it for myself, as the act of singing, and performing in general, in its physicality and emotional investment, has always helped me really alive, and having survived COVID had made me feel even more motivated to embrace that feeling. A few days later, I got on the phone with John Spiak, who is the Director and Chief Curator of the Grand Central Arts Center at California State University, in Santa Ana; he was concerned about my health and wanted to check in. We both share a long history due to our involvement in the socially engaged art movement in the early 2000s. We had been in conversation over the past years about me doing an artist residency and/or project with them, but we had not come up yet with a plan. We started discussing what we could to do help people cope with the terrible social isolation that the quarantine had imposed on all of us, all over the world. I mentioned that I had done a singing telegram project back in 2001, which had proved very popular, and thought this format could work again. I had presented it as part of the Brewster Project, a weekend-long conceptual/performance festival organized by Regine Basha, Christopher Ho and Omar López-Chahoud; it had been my first socially engaged art piece. Singing from the local bar, I had a line of local townspeople who would commission singing telegrams that I would deliver by phone anywhere in the world (at that time we would use international phone cards). The singing telegram format was invented during the Great Depression by George P. Oslin, then PR Director of Western Union, when he had the idea to ask an operator, Lucille Lipps, to sing a happy birthday telegram over the telephone. Because telephone technology was not widespread still in the early 30s, telegrams were usually delivered (i.e. sung) in person. The cheerful (as well as the human, and personalized) nature of the sung telegram was enthusiastically embraced precisely at a time when society needed much cheering up. John was very enthusiastic about the idea and in no time we set up a system to offer free singing telegrams via Zoom to anyone who wanted it. Because we all were in lockdown, John became in many ways the curator, manager, designer and project assistant all at once, designing the website, setting up zoom calls and so forth— in other words, he was a one-man orchestra while I was a one-man production. We thus launched the Grand Central Singing Telegram Co.

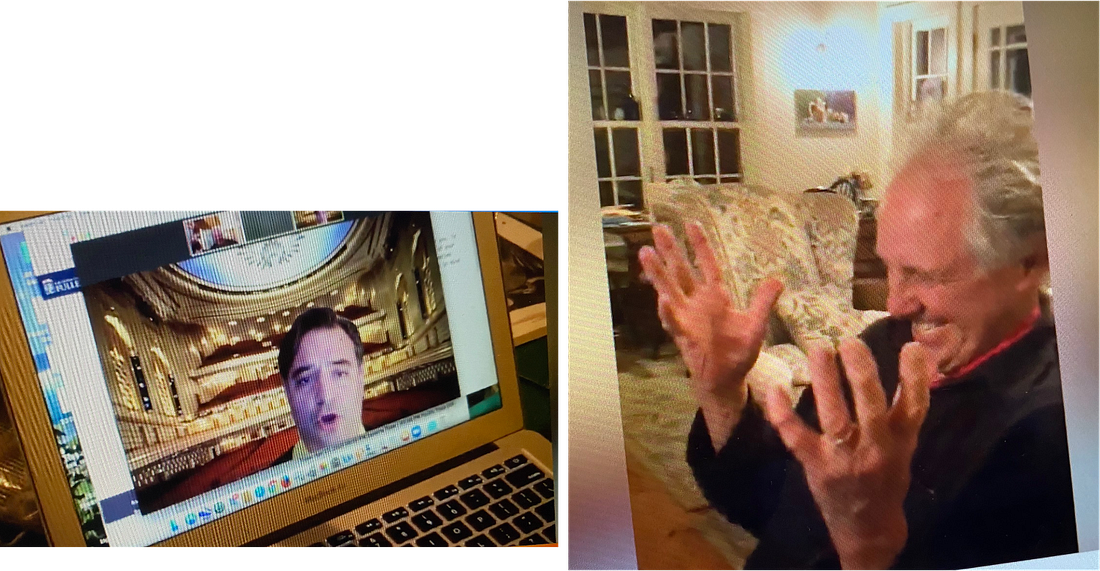

I developed a menu of songs that people could choose from— which was, in essence, an autobiographical account of my musical affections. I started singing at age 11 or 12, Neapolitan songs first (after I practically memorized all the tracks of a cassette tape of rather defective recordings by Beniamino Gigli that my brother had recorded over the radio). I spent many evenings with my aunts who were big opera fans, where I practically memorized Carmen, The Tales of Hoffman, La Boheme and Turandot among many other operas. I wanted to be an opera singer at 13. In high school I learned Mexican folk music and clumsily learned to pluck a guitar. At 18 I played Tony in a high school production of West Side Story and was into Broadway. The menu included all these selections. I dressed like a Western Union telegraphist and created an opera stage background for visitors. Orders would include a message from the sender and the song I deliver. When promoting the service, I usually joked that I was not Plácido Domingo, but I was free. The number of requests we received far exceeded our expectations. The schedule for telegram deliveries, which was organized into 10-minute slots, filled up almost immediately. I transformed my daughter’s room into a makeshift stage/studio, where I delivered the telegrams every evening, right next to her hamster. I typically started around 8 p.m., after dinner and a couple hours after the 6 p.m. clapping in neighborhoods to show appreciation for healthcare workers. The process soon became routine, with many popular Hollywood and Broadway songs being requested: My Favorite Things, Moon River, Somewhere Over the Rainbow, and Somewhere were among the top choices. Opera lovers often selected Nessun Dorma, Vesti la Giubba, and E Lucevan Le Stelle, while those with a preference for Mexican popular music frequently requested La Llorona. Each day, John would provide me with the schedule, and I’d log into the Zoom link as the guests began to appear. Most of them were recipients of a gifted telegram, often unsure of what to expect, though sometimes they had requested the telegram themselves. While a few friends and acquaintances placed orders, the majority of the time I was connecting with strangers—people I had never met and likely never would again. There was something strangely intimate about these encounters, almost secretive and X-rated, as I sang intensely passionate and often heartbreaking songs, just me and the other person. The messages I delivered often moved people to tears: it was easy to forget just how deeply the isolation of the pandemic had affected so many. I sang so many telegrams that many have faded from memory, but John reminded me of a few. "I clearly remember you sharing the story of delivering a telegram to Brazil for a young boy's birthday," he said. "The joy and excitement on their faces when you appeared on screen were unmistakable. The whole family was engaged and deeply touched by your heartfelt performance." I sang to a baby, to an elderly woman in her 90s somewhere in Italy, to a gay couple, and to a giant raucous party in Caracas. I sang Sinatra to a college student on behalf of her parents, to someone’s aunt in Santo Domingo, and to my old high school theater teacher who had directed me in that production of West Side Story, per request of her daughter. I was even invited to sing a telegram live on KTLA Morning News for one of the anchors celebrating his wedding anniversary. I sang to a woman who kept very quiet and thanked me politely at the end, and after I said good night, she replied, “it’s morning here in Singapore”. Yet another request was for a very difficult 19th century gospel hymn that took me a long time to rehearse; the mysterious participant did not turn on his camera. I performed, and at the end, he simply said, “thank you”, and left. A scary moment for both John and I was when Western Union contacted us. We were afraid of receiving a copyright infringement lawsuit as, unbeknownst to us, the Singing Telegram is a trademark. They, however, wanted instead (and perhaps thought it would be better business) to sponsor us, which we of course welcomed. I asked John whether he thought if what we had done had been a social practice project, given its contact-less nature. “Absolutely”, he said. “The entire process involved direct interactions: an individual ordering a singing telegram for a friend or loved one, the recipient receiving a surprise email notifying them of a scheduled singing telegram, and then you showing up to engage and interact directly, delivering their message and singing the selected song.[…] It wasn’t a passive experience; you engaged with each of them briefly after the telegram delivery, creating a socially engaged moment of connection.” A year or so ago I was conversing with the composer David Lang about our work in teaching in the performing arts higher education field, and how students usually zero in on a single, ambitious career goal: being a soloist, a star — which is an unlikely goal for even the most talented. “I always try to show them— Lang said— that there are so many other ways to make music, to imagine a career— making , for example, performances in your apartment.” Reflecting on his words, I now realize that I had unknowingly stumbled upon a form of modest alternativity. It was as though I had been guided by the hand of Don Giovanni’s Commendatore, not dragging me into hell, but instead, gently led onto Zoom to perform on a makeshift stage. I wasn’t one of the heroic doctors we cheered for every evening; rather, I had the humbler task of reminding others that they were not alone. Invite your friends and earn rewardsIf you enjoy Beautiful Eccentrics, share it with your friends and earn rewards when they subscribe. |