Why Can't Americans Take A Vacation?Excepting the Dish, of course. But I'm still kinda European I guess.(This is adapted, and slightly updated, from a piece I wrote for the Sunday Times of London, back in the summer of 2001, a month before 9/11, trying to explain to vacationing Brits why Americans work so hard. Re-reading it, not much has changed.) I guess I know I’m now fully an American when I bought a beach cottage on Cape Cod, moved here in early May, and haven’t taken a day off work since. No, I’m not looking for sympathy. I’m beyond blessed to be able to work within walking distance of a beach. But there are moments when I wonder why I can’t really bring myself to, you know, take a holiday. And then I look around me at all the hustle and bustle on the Cape, the phones trilling late at night in restaurants, the packed social schedules of networking East Coasters, and I realize that, compared to most of my peers, I’m a slacker. Even here, even with miles of empty dunes and clapboard cottages, even with sunsets that give a neon glow to the small boats bobbing in Cape Cod bay, even in the beginning of August, the work must go on. Actually, the absence of August is the least of it. The truly remarkable thing is how crammed with work the rest of the year is. Juliet Schor, author of the now-classic tome, The Overworked American, calculated 20 years ago that American manufacturing workers work 320 more hours a year than their counterparts in France and Germany. If you add in necessary chores at home, the average American spends over 55 hours a week working. Many women, who juggle children, jobs and housework, can be toiling for up to 90 hours a week. They basically work, eat, watch a half-hour of TV, and sleep. The irony is that, as Americans’ standard of living has soared, Americans have not taken that as an opportunity to rest on their laurels. The average standard of living is way higher than in any European country — and the median standard is even higher. The last two decades have only magnified the gap, as Europe lollygags behind. But the actual quality of life — i.e. the amount of time people spend just chilling out and goofing off — is arguably far lower than in cushy, lazy Europe. Between 1970 and 1990, Schor calculated, the average American added 163 work hours to their lives — about an extra month. (Oh, that’s where August went.) But this number disguises the impact of feminist triumph. In those 20 years, while men added a meagre 98 hours a year, the average woman added a total of 305 hours — a whopping seven-and-a-half extra weeks on the job. No wonder George W Bush had to find all sorts of activities to distract from the notion that he was actually taking a break from work for a month on his ranch in Texas. It’s a “Working Vacation,” we’re told, which is as quintessentially an American oxymoron as you are likely to find. He’ll be touring the country, touting faith-based social work. He’s already spent some hours volunteering as a construction worker for Habitat for Humanity, the charity for the homeless. He spent the first week of his break preparing his speech broadcast on Thursday night, endorsing limited federal funding of stem-cell research. A bevy of senior aides are hovering around, giving the impression of business. Meanwhile, on the steamy East Coast, the New York Times has been goading the president into cutting short his vacation. The editors pointed out that most Americans get two weeks off a year. There’s no European August collapse over here. Globalization and technology have only been making matters far, far worse. The shake-out of the early 1990s and the Great Recession led to much more streamlined workplaces, more efficient workers, more international competition, and, yes, more work. To make matters worse, the new economy was even more punishing than the old. Technology that allows you to work from home, however comfy it sounds, means that people are never off-duty. Phones beep them late at night; bosses call them early in the morning; emails demand attention, wherever you are. It says something, I think, that we have to designate only one carriage on a train as the “quiet car.” Even then, the quiet is effectively a low soft drumming of typing on laptops. And then when Americans get an hour to kill, what do they do? They work out, of course! Every serious upwardly mobile human being in major American cities has a gym membership, where he or she can dutifully “work” out. In Washington, you can look in and see rows of young interns and careerists in the local gym, taking spinning classes, where they go immediately after work, pedalling furiously on stationary bikes, interrupted only occasionally by an incoming call, or a social media notification. Back in the 1990s, even the name of my gym had a Puritan ring to it. It’s called “Results: The Gym.” If you want to find a reason for all this, you can state the obvious. Americans like more things than other people. And they like their things bigger and better and newer than most others. The only way to keep up with the frenetic Joneses is to be even more frenetic. So work they must. Census figures show that in the last ten years, Americans have far more of everything than they have ever had before. Ninety percent own a car, almost 20 percent own three! Houses and cars have simply become bigger and bigger. The average suburban car now resembles something like a small tank. The 1990s also saw the introduction by McDonald’s of the Super-Sized portion. A small European army could live off it. And the vast and increasing bulk of Americans only ensures of course that the cars get bigger and the houses larger. Not to speak of the gym memberships required to burn all that fat off. All of which costs even more money, which means more work. But perhaps the deeper reason for the frenzy is that work is still the most reliable integrator of American society. As the culture continues to resemble a multi-ethnic, multi-cultural tapestry, work is the thread that keeps it together. It’s an ethic that provides the rationale for economic inequality and an ethic that guarantees continued economic growth. It also keeps people from thinking too much, for which many Americans are deeply grateful. Working hard is simply what they do with their lives; and it’s what every member of an alienated minority — from immigrants to welfare recipients — does to integrate more fully. It’s what it means to be middle-class; and being middle-class is what even the rich and privileged aspire to be. Just look at that American scion on his Texas ranch. Even dauphins are drones here. Back On The Dishcast: Michael MoynihanMoynihan is one-third of The Fifth Column — the sharp, hilarious podcast he does with Kmele Foster and Matt Welch. He was previously the cultural news editor for The Daily Beast, a senior editor at Reason, and a correspondent and managing editor of Vice. It’s a fun summer chat with an old friend. We recorded it a few weeks ago, on July 24. Listen to the episode here. There you can find two clips of our convo — on the conspiracy theories of RFK Jr, and the deepening rift within the Israeli government. Since the convo also covers Orwell and Hitchens, we reprinted a back-and-forth Hitch did with me and Dish readers on everything Orwell in 2002. He had just written Why Orwell Matters, and if you want to read Hitch at his conversational and argumentative best, the dialogue is fascinating, super-smart and occasionally hilarious. I’m proud to disinter it 20 years later. It remains as fresh as ever. Home NewsThe Dish is starting its annual summer vacation after today. We’ll be back September 1. I turned 60 yesterday, and am going to absorb that terrifying fact in the tidal pools at the end of the Cape for a while. Back with bells on by the end of the month. As our annual renewal period comes to a close, a final thanks to all of you Dishheads who have kept your paid subscription for the coming year. Many of you have emailed asking how to change your credit card, which may have expired this past year. Here’s the link to do so. And you can change your email address here. From a subscriber in Asheville:

If you are among the 130,000 readers who get the free Dish every week but haven’t yet subscribed, we would appreciate the support. I can’t tell you how often someone comes up to me and says they love the Dish every week, but when I ask them if they’re a paid subscriber, they blush a little, say they meant to subscribe, but never quite got around to it. And I know how you feel. It’s the kind of procrastination I’m particularly prone to. So consider this a nudge: The full Dish includes extra posts from me, the hugely fun window contest (here’s an example), a weekly digest of all the other Substacks worth reading, and the full, uninterrupted episodes of our weekly podcast — with no ads! But a paid subscription has something else: a civil, lively, anonymous and edited debate between me and the readers, and the readers with themselves. Think of it as an antidote to Twitter. No grandstanding, no abuse, no screaming, but a fair selection of arguments from far left to far right, on every topic you can imagine. Dish readers, we know, are the best on the web. They have expertise, experience, and nerve. They’re Democrats and Republicans, liberals, conservatives and leftists — a mix almost absent elsewhere. They hold me to account. And if we want to preserve that kind of open, liberal dialogue in this republic, we also need to support it. So join us. Around a buck a week, or just $5 a month, or $50 a year — and you can cancel at any time: Touching GrassA reader writes:

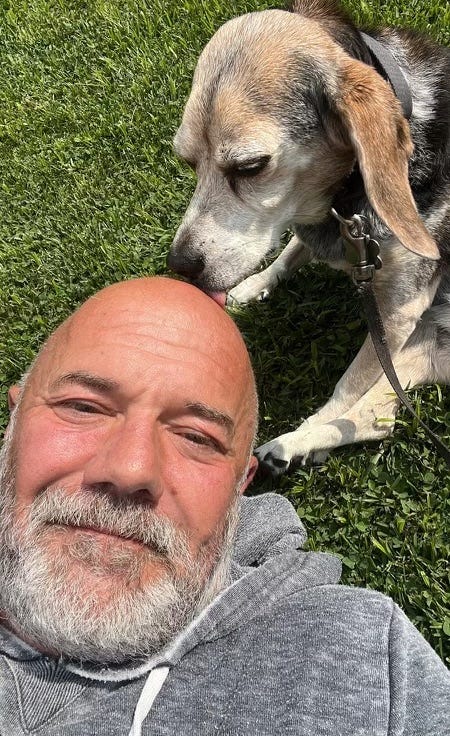

Awesome. The reason I found Bowie is the Dish. I got an email a little bit after Dusty died, from a Dish reader who temporarily fostered dogs, on their way to potential adoption. She said she had a young, triped beagle puppy, about a year old, who had to be in a crate most of the day and needed an owner. Would I meet her? Aaron said no: we already had our second hound, Eddy, and we were living in New York City in a tiny apartment. I told him I’d just go and meet the dog and wasn’t committed either way. He told me that as soon as I saw a handicapped little dog, who’d been hit by a truck, I’d be incapable of walking away. And he was right. It was among the best decisions of my entire life. She was skinny as a rake, and instantly lovable. She managed her disability like most dogs do — with aplomb and indifference. And for the next ten years, she had almost no issues until a month ago, when her back leg went out completely. She fiercely resisted the little chariot I got her, and I resigned myself to patience and hope she could recover. She has! After keeping her confined, or on very short walks, she rested and healed and is now almost back to normal. She has always amazed me, and still does. Another rescue-dad has some thoughtful advice:

I’m going to keep all this in mind, as she gets older. Bowie is not that social with other dogs but super friendly with people, so the dog park option probably won’t work. But I’m so grateful for the tips. Another concerned reader also “wanted to offer suggestions for your beagle”:

The View From Your Window ContestWhere do you think? Email your entry to contest@andrewsullivan.com. Please put the location — city and/or state first, then country — in the subject line. Bonus points for fun facts and stories. Proximity counts. The deadline for entries is Wednesday night at midnight (PST). The winner gets the choice of a View From Your Window book or two annual Dish subscriptions. Mental Health BreakThe bear days of summer:  See you on Friday, September 1. Have a lovely August — and, if you can, have a great vacation. Invite your friends and earn rewardsIf you enjoy The Weekly Dish, share it with your friends and earn rewards when they subscribe. |