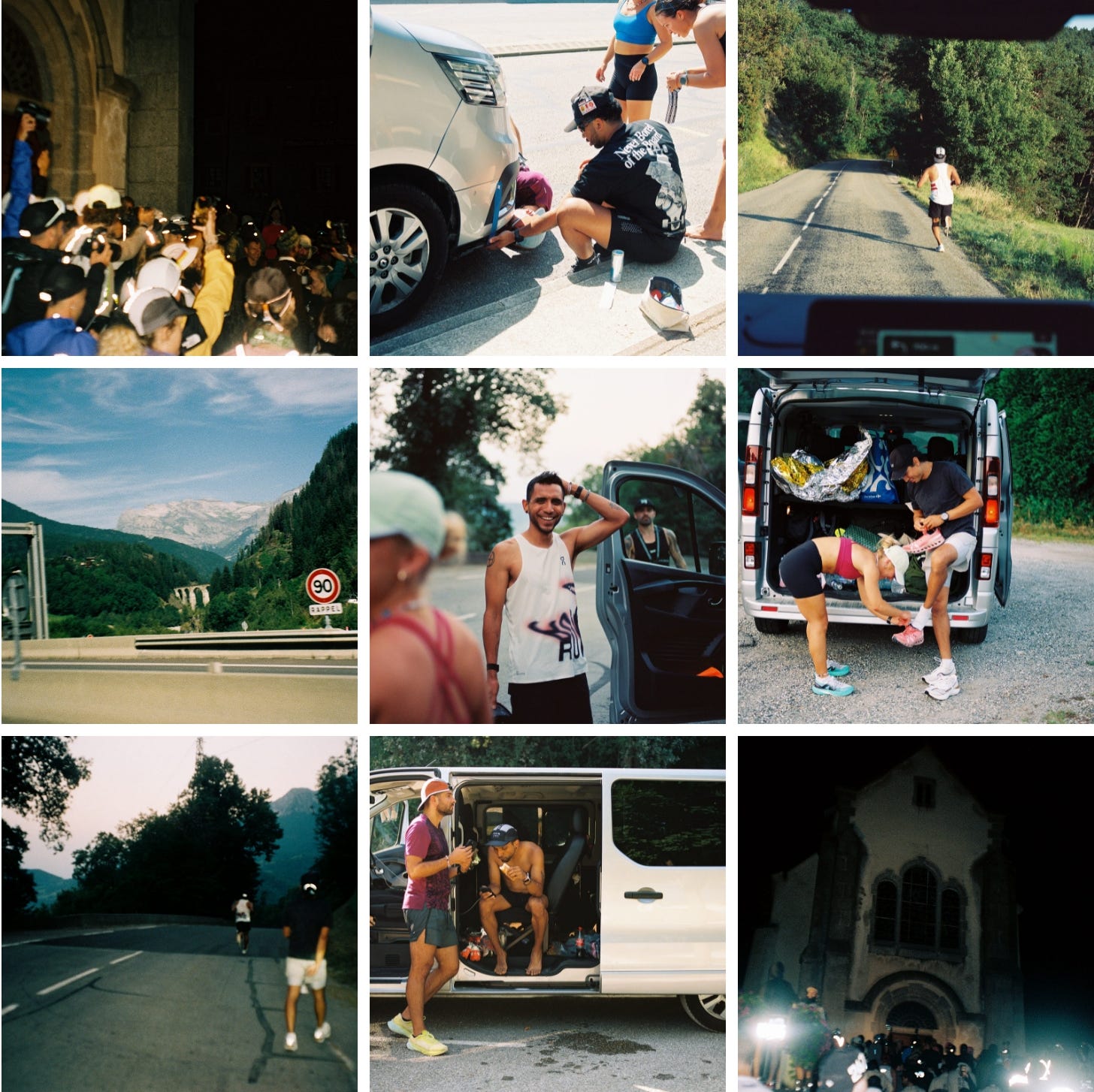

The Speed Project Goes AlpineRunning from Chamonix to Marseille: The Feral Angels take France. A 2024 race recap and why I wasn't there this year.TSP raced in France this past weekend, and I’m having FOMO, so here is a look back at last year.

When one tugs at a single thing in nature, he finds it attached to the rest of the world. ― John MuirThe problems started almost immediately. The logistics seemed snake-bit. Once we arrived in Chamonix, my husband turned to me and asked why we hadn’t just flown into Geneva, an hour’s car ride away, instead of the 19-hour multi-leg plane-train-automobile trek we had made from JFK to Paris to Marseille to the mountains¹. We had reasoned it made sense to travel with the rest of the team from the finish line to the start line so we could get a sense of the course. In theory, this sounded like a good idea. In practice, we were all half-asleep with jet lag and started the drive so late it was too dark to see much of anything on the course. We arrived in Chamonix in the dead of night, almost exactly 24 hours before we would congregate for the start of a 290-mile race with over 6,000 ft of elevation.  With our one day under Mont Blanc, we went to the safety briefing, the grocery, the UTMB start line, and a few good restaurants. We were more naive than we should have been. The returning Feral Angels were still riding the high of having won the women’s field at LALV. Our team was very fast, and we knew we would be racing competitively. We were on the same page going in: Dogfight to the finish. But, in the fray of things, the plan for getting out of Chamonix was left for the morning as a game-time decision. This proved to be treacherous. We got lost almost immediately, sending some of our strongest legs up masochistic inclines for nothing. We fought to get back on track, regained our footing in the midst of the pack, then pushed through the day trying to make up ground on the frontrunners. The fighting and snide comments started almost immediately as well. “Do you even know how to navigate?” One of our runners asked me after finishing a grueling trail segment in the pitch black that I had sent him on after taking the map to get us back on track². Gabe, our driver, was a saint, and on the receiving end of most of the blowback from our combined exhaustion, nerves, and growing distrust of each other. Rory, our team's multi-media producer, held it down and tried his best to keep us on track as emotions flared. We were unfair to each other.  But we also helped each other in the ways we could. Nikki organized everything from the hotels to the meals to the van, we could not have even started without her. Gabe drove something like over 24 hours straight. Steve made everyone sandwiches in the back of the van. Halle was probably the only one of us whose positivity didn't waiver. Zach stayed level-headed and led the team with focus on the Secret excursion getting us down the side of a mountain. Rory made us look better than we did. And Adrian was the king of one liners: “It doesn’t matter how bad you feel you can always eat a croissant” “GET OUT OF ME DEMON ACID” “This is a different kind of hell. Who’s going to carry the YACHTS motherfucker.” “A leetle bit of good a leetle bit of shit” The sun came up and went down and we ran. It was more difficult than expected. The alpine air was thin and cold, and burned our lungs, or mine at least³. Any time we started to find a rhythm as a team, it seemed like we would get lost again. The guide to the course was frustrating, sending runners through confusing sections of terrain in the dark that required professional technical ability. “If I’m on my hands and knees having to climb, I don’t think you can call that running,” said another of our runners after a trail section that luckily we reached after we had regained contact with the rest of the teams, so they didn’t have to navigate it alone. I honestly don’t think even if we had made a concerted effort to go over the maps more carefully beforehand if it would have made any difference given how the dark changes things. We ran and slept in shifts, with three of us in the back row seats of the van while the pod running rotated out from the front row. When moods were high, it felt like being kids at summer camp, getting away with something. We were explorers, flying on our feet. But as night fell and energy lagged, it began to feel tight and suffocating. It didn’t help that as we approached halfway, reports started to pour in on the WhatsApp group that the French police were onto us and stopping teams they caught on the road (one of our runners was eventually stopped and questioned but released without incident). This set everyone on edge and became a constant source of anxiety, humming in the background like radio static. We thought we knew what we were signing up for. Almost all of us had some kind of ultra-running or ultra-relay experience. And five of the eight of us had just raced the Southbound 400 together, which had been hard, but the team had had a reasonably good time and solid camaraderie. This wasn’t our first rodeo. But TSP is a different animal. With a race like TSP, there are constant warnings and reiterations of the fact that the weakest point on any team comes down to each individual runner. In our pre-race meetings, long before we got to France, we reminded each other and ourselves that it would get tough and hard, and to be gracious to each other when that point came. But this was the first time that point really made itself known, to me at least. Of the multiple ultras I’ve done, this is the only one where communication fundamentally broke down to the point that the team dynamics were shot to hell, and we were hurting more than helping each other. You don’t know how you’ll react until you get there. I did not react well, and I’ll own that⁴. You never know what someone else might be going through and what a race can bring to the surface.  I’ve been thinking a lot about the relationship between speed and intensity—how a car going 25mph getting in an accident, not usually a biggie, but a car going 100mph getting in an accident? Different story. Any issue, no matter how small, is going to be magnified when under pressure for 500km. The harder and faster you’re going, the more it will hurt if things go awry. If there is one thing the Speed Project can guarantee, it is that things will go awry. It’s still worth it. No coal, no diamonds. Ultimately, we made it to Marseille safely. As a team, we even added the SECRETS side-quest, an extra eight-mile summit excursion with 1,600 ft of elevation, at the last minute when we could have just headed for the finish. It was the most beautiful race I’ve ever run, even if it was the most difficult, or maybe because it was the most difficult. I do think it’s a testament to the character of our team that even with everything that went wrong, we pulled together at the end to get to the finish line. I’m pretty sure we all ended up running over 50 miles each. For a while, I felt sick with guilt and shame over this race. That I had failed morally as a human being for not being better in the face of adversity. I fixated on it and what I could have done differently. I didn’t want to write about it because it felt like airing dirty laundry (and who would want to admit they failed?). But then I listened to the MakeRunning podcast recapping other teams’ TSP experiences. I was blown away by Matt Wiersum’s interview, hearing that even the best and most seasoned teams fall prey to the exact same dynamic challenges we had faced. To her credit, this was the most intense and fastest team our captain, Nikki, had recruited and pulled together yet (she went on to bring together an even stronger team for LALV SECRETS ’25 that was absolutely killer; she is an incredibly savvy organizer and leader when it comes to bringing people together). It was awe-inspiring to see how hard these runners could go. OF COURSE, everyone is going to be high-strung and run a little hot in the thick of competition.

Learning that we were not the only team to deal with this type of fallout and dysfunction was an immense relief. That’s not to excuse the problems, but it softened the edges a bit. It felt like a failure, but it wasn’t fatal. Or anomalous to the project as a whole. The most important gear you can bring is gratitude and relentless positivity—pretty much nothing else matters if you can stay aligned on those fronts⁵. Having a year of perspective and a few more long-distance solo races under my belt helps as well. Some races ask questions, and some races answer. I do think it’s true you learn more from your defeats than your victories. I wish I had gotten back to running sooner rather than dwelling in the sense of defeat following Chamonix. Running alone can be redemptive, but doing so in community is even better.  I didn't get a glamour shot of Gabe so he is missing from this line up, but a special thanks to this team for getting through the darkness and getting it done. Rory, Steve, Nikki, Halle, Zach and Gabe, I'm grateful we finished together. Feral forever. I had originally planned to try and redeem this race by taking it on solo, and it was among the many applications I sent out into the universe last spring. I ended up getting into grad school, which I start next week, so the timing didn’t quite work out, unfortunately. But as always, it was better next year. Links!If you are in LA, run with Nikki! Check out her class at the Nike Running Studio in Santa Monica. She’ll make you a faster runner and a better person. Watch Rory’s film of our time in France:  “In 2024 the electrolyte drink market was valued around $38 billion.” According to the NYT, which asks if you even need them to begin with. Several people also sent me the NYT reporting on runners being more likely to have colon cancer, to which I turn to Alex Hutichinson to make sense of it all: “At this point, it’s simply not possible to say with any confidence whether the new results signal a genuine danger, whether they’re a statistical fluke, or whether there’s another explanation.” H/t to carl maynard for this one: A female Scottish ultra runner finished a 100-mile race so far ahead of the next competitor that she was home before he arrived at the finish line. 1 It should be noted that while he complained about the trek there, he spent most of the trip eating steak tartare with wine and cheese at the ski chalet, while I was having the most miserable racing experience of my life 2 Not to be defensive, but I did get us back on track, eventually 😭 3 I felt a profound sense of loss as we left the mountains behind. Maybe if I had not spent the last year rotting my brain staring at my phone, I would have something poetic to say about the mountains, but they defy my feeble attempts to convey their majesty. The truth is, the altitude made me feel sick and weak. When we took off down the course, it felt like I spent the rest of the race trying to access the higher gear of my fitness, and never quite finding it. 4 As a result, I took a big step back from racing for the rest of the year to do some soul-searching in self-inflicted penance 5 Having a second support vehicle where people could cool off and take a breather would also have made a HUGE difference. Attitude is everything, but if your budget allows and you can set yourself up to mitigate as much friction as possible, do that!!!!! Thanks for subscribing to Feral Angel. This post is public, so feel free to share it. |