While excellent newsletters on specific themes within public policy already exist, this thought letter is about frameworks, mental models, and key ideas that will hopefully help you think about any public policy problem in imaginative ways. If this post was forwarded to you and you liked it, consider subscribing. It’s free. #230 Performative Politics is all the RageFTC vs Amazon, Bandh Politics, Kaveri water-sharing mechanism, Disappearances in China, and MBBS seats policyWTFProgramming note: We’re taking a short writing break starting next week. The next edition will hit your inboxes on 28th October. Global Policy Watch: Amazon, Prime Target?Global policy issues relevant to India— RSJIt is time to rewrite those case studies about Amazon and its relentless focus on customers. On Tuesday, the Federal Trade Commission and 17 state attorneys general sued Amazon, alleging that it “uses a set of interlocking anticompetitive and unfair strategies to illegally maintain its monopoly power”. Here’s more from the FTC press release:

I had to reread that line slowly. You can never be too careful at my age.

I wish I had such confidence in the future impact of my current work. But what do I know? Anyway, I searched a bit on the web for customers complaining about Amazon’s extortionary prices and its terrible customer service record. Let me just say the results weren’t dissimilar to looking for flat earth believers. Sure, there was a vocal minority out there who believed in such things, but no one took them seriously. So, what exactly is the FTC worried about? Well, going through the FTC lawsuit, I arrived at broadly three conclusions. One, Amazon is making life difficult for the many small companies that use its platform to sell its products. Amazon takes almost 50 cents for every dollar sold by them as fees; it punishes the sellers if they sell their wares cheaper on any other site by blacklisting them or making them invisible on their site, and it forces them to use its expensive logistics network. Amazon has a monopoly in online commerce, so sellers are, therefore, forced to raise their prices or cut corners on the quality of their products and list their products only on Amazon. This is bad for consumers who don’t know these things yet. Two, FTC believes Amazon uses its dominant position to forcibly bundle products and services across its retail, video streaming, healthcare, cloud and search services. The famous Amazon ‘flywheel’ seen differently is a closed loop that traps customers and sellers alike and restricts their choices. Over the years, it has bought out competitors, edged out offline retailers by pricing below cost and has become the only real option for online retail. Three, the FTC is asking the courts to look beyond the immediate horizon and ask where the customers will end up with Amazon. To them, it will repeat its supplier playbook on the customer side when it knows it has closed down most other options for them. By then, it will be too large to tame, and the customers will be at its mercy. Why are they so sure about it? Well, just look at how Amazon investors think about its future. The only reason it has an astronomical price-to-earnings ratio of about 100 (TTM) at its size is because the investors believe it is a “winner takes all market” where eventually it will rake in supernormal profits like a monopoly. Even if Amazon fills up every page of its corporate values handbook with its desire to be fair to its customers, its investors will drive it to a very different destination. I have a few tangential points to make before I come back to these arguments of the FTC. First, this isn’t a direct strike against Big Tech that the FTC has promised. This is a case against Amazon, the retailer, with a view that if the FTC is able to make a case for monopoly here, it will derail Amazon’s big tech ambitions elsewhere. But the pointed case against Big Tech's monopoly of user data, ads, and information and behaviour manipulation is a different beast. There are parallel cases going on against Google, Facebook and Microsoft by various arms of the federal government, but a unified case against them is still to be made. Second, the FTC has been going after big targets and failing in the recent past. In July, a US federal judge rejected the commission’s attempt to halt the $75bn acquisition of video game maker Activision Blizzard by Microsoft. It was a high-profile and visible antitrust challenge which was pushed through with somewhat lame logic. This came after another of the FTC’s moves to block Meta from acquiring Within, a reality fitness startup, was defeated in court. This brings me to the third point about the extent to which a regulator must be driven by ideology. I mean, it is human to have biases regardless of the position you hold, but in this case, Lina Khan has built her career based on a certain ideological opposition to Big Tech in general and Amazon in particular. The regulator is expected to draft guidelines that are prudent, protect the interests of citizens, and that can stand the test of time. There must be some way to have the feedback loop of the losses in courts restrain ideological overreach by the regulator. We have had multiple instances of the damaging consequences of such ideological certitude among the regulators, with exhibit A being Alan Greenspan’s devotion to the ‘Ayn Rand’ school of objectivism. Lastly, with US presidential elections about a year away, whose conclusion is far from foregone at this moment, it is pertinent to ask if such moves by the FTC are more performative than substantial in nature. It will be a pity but not unprecedented if regulatory actions are driven by an instinct to play to the gallery for short-term electoral gains. Coming back to the substance of allegations made by the FTC against Amazon, it will be useful to understand how the thinking on antitrust has evolved over time. It has never been easy to define a monopoly and have a list of practices that the FTC must regulate from an antitrust perspective. The days of a single provider of a product or service like AT&T, U.S. Steel or Standard Oil are long gone. Easier access to capital, democratisation of technology, and access to global markets have meant the process of creative destruction is ongoing in every sector. If you take a look at the top 10 companies by market cap 50 years ago and compare that with the list today, you will have your answer on how vulnerable companies have been to the forces of market and competition. Therefore, over time, most antitrust regulators have concluded that the best way to assess monopolistic practices is on the yardstick of consumer welfare. In a way, in a monopoly-like situation, it is the residual value that’s visible after other stakeholders like investors, suppliers and employees have extracted every ounce of profit for themselves. This might not be the best way to measure this, but like most things in life, it is the first among the bad options available. Only if customers are being extorted and they are complaining about a lack of choices, then the antitrust regulator must act. Every other complaint can be brushed aside. If you give suppliers free rein, they will complain about how every large customer forces them to lower their prices. Should you start believing it to be true and force those companies to let their supplier dictate terms? Soon, you will have employees complain about low wages. Will that be a reason for intervention? And if you do intervene, what will happen to the prices for customers? As history has shown repeatedly, these are bad ideas and almost always counterproductive. Then there’s the argument that Amazon is biding its time now and it will abuse its dominant position in future. The customers will have nowhere to go then. There are two problems here. One, will we now anticipate crimes and start prosecuting on the basis that they will happen in future? This is quite Orwellian. Two, it goes against everything that we have seen in the past half a century of disruption. Every decade since the 1970s, we have been led to believe that a handful of companies will have a monopoly unless stopped through regulations. The regulators didn’t have to break them up. Agile challengers with disruptive ideas and access to capital and free markets were good enough to restore the balance. I see no reason why it will be different this time. In fact, in my view, based on empirical evidence, by the time the antitrust regulators go after a company, its game is up. It is too large and flat-footed already and, left to itself, will struggle to compete. I also hope that in this process, Amazon counters the FTC’s allegations about how it shortchanges its suppliers and small businesses with data on how it has enabled ordinary people to start businesses of their own. The Amazon platform has made entrepreneurship easy. Anyone who has tried to list their business on it will tell you about how superior it is to any other available platform. It is easy to cherry-pick data to show the suppliers are getting a raw deal. The number of entrepreneurs from small towns in India with no background in business who have been enabled by Amazon is huge. It will be useful to see the net impact of what the platform has enabled in the SME ecosystem. Back in 2017, when Lina Khan was a student at Yale Law School, she wrote that one paper on Amazon that eventually led her to be the chair of FTC today. In that paper, she argued that Amazon has evaded regulatory scrutiny by devoting its strategy and rhetoric to reducing prices for consumers by pursuing growth and pricing below cost. Now, FTC, with Khan at the helm, is alleging that Amazon is forcing third-party sellers to raise the prices for consumers by extorting value from them for being on the platform. It doesn’t sound particularly consistent to me. I guess people have a right to change their argument over time. But I suspect this is the old case of having only a hammer in your hand. The whole world appears as a nail, then. India Policy Watch: Same Old Stock ResponsesInsights on issues relevant to India— Pranay Kotasthane Let’s agree that last week wasn’t the finest one for Bengaluru. There were two botched-up bandhs on Tuesday and Friday. In between, a harrowing traffic jam on Wednesday crippled the city’s Outer Ring Road (ORR is a tri-misnomer — it’s neither in the outer areas nor in the shape of a ring, and sometimes, not even a road). Trevor Noah’s show was cancelled because of outrageously shoddy event planning. And then, there was the laughable ban on carpooling apps based on complaints by taxi unions. I’m not going to rant about how badly India’s best city is governed. That much is well-known for decades. Instead, I will address two issues in this edition: bandh politics and Kaveri water-sharing. A bandh or a forceful shutdown is unconstitutional, whereas a ‘peaceful’ strike is legitimate, according to the current legal rulings. And yet, there’s a sufficient grey area between the two, allowing various groups to deploy ‘bandhs with strike characteristics’ without much trouble. Given that they are a reality, it’s useful to think of the various political purposes they are intended to serve. I found this definitional clarity in Bandh politics: crowds, spectacular violence, and sovereignty in India to be instructive:

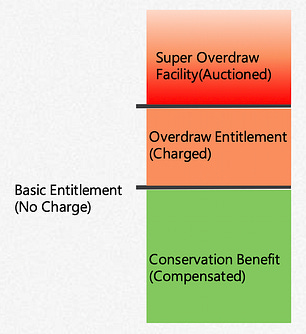

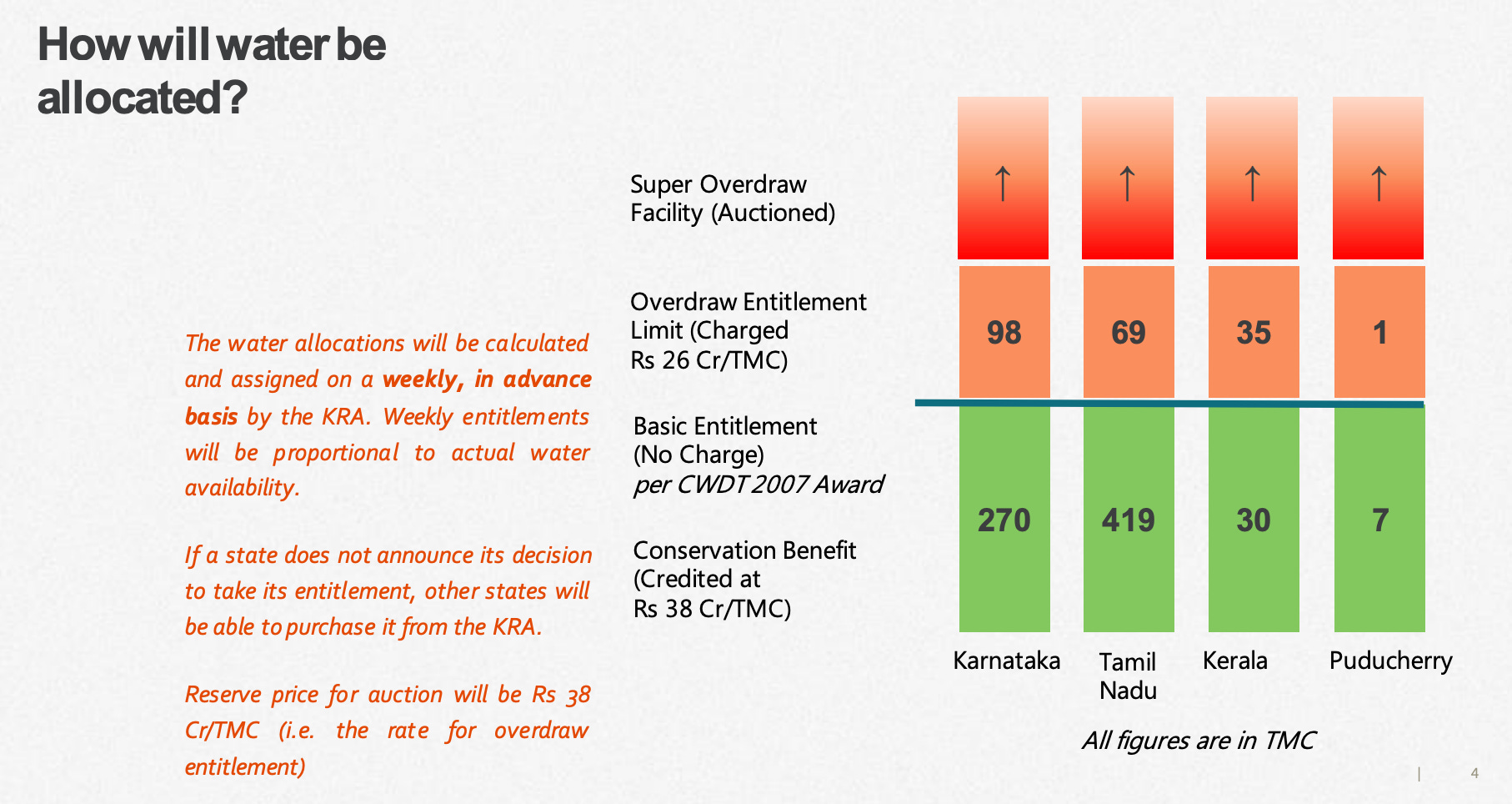

This performative act of disrupting every life to direct the wider public’s attention towards a particular cause is deployed for several political purposes. The first (rather obvious) purpose is to bring a group’s demands to the front and centre of politics. For instance, we had another bandh earlier this month in Bengaluru by private transport unions who were protesting the state government’s decision to make public transport free for women. Causing inconvenience was both the means and the end. Since this particular bandh was called in direct opposition to a government flagship scheme, the government was directly incentivised to negate its effects. It deployed police to prevent forceful shutdowns and ran additional public transport services. In the continuum between bandh and strike, that protest ended up looking a lot like a strike rather than a bandh. Another purpose could be the use of a bandh by a government as a CYA operation to shift blame to another entity. For instance, if the government supports a forceful closedown of its own cities to protest a court decision, the performance is intended to express displeasure and convey to the people that it wasn’t responsible for this situation and has no choice but to comply. What I haven’t understood is how frequently governments are able to pull off the “we are inconveniencing you, but for your own interest” act. A third purpose could be to question a government’s legitimacy and authority. If a large number of people “observe” the bandh, the protestors can claim to have threatened a government’s right to govern in a visceral manner. There are shades of both the second and third purposes at play in the bandh instances of the past week. The fact that there was prompt policing, no large-scale violence, and no damage to public property indicates that it was not the government which was the primary force behind the bandh. But the government’s vacillating position on the call for bandh itself indicates the second purpose was at play, too. Regardless of the purpose, the crucial point is that the bandh did cause immense economic damage. Karnataka Industry bodies claim that the two days of bandhs cost nearly Rs 4,000 crore to the state’s GDP and a Rs 100 crore loss to the state GST account. Forty-four flights were cancelled. While the affluent few—primed by the COVID-19 experience—swiftly shifted to working from home, the losses would have been higher for people who can’t afford to do that. Despite the de jure proscription of bandhs, they remain an odious political reality. The bandh, though, was symptomatic of a much larger problem. It again exposed the lack of ideas on Kaveri water management. Despite the regularity with which this situation reoccurs, little attention has been paid to addressing this problem sustainably. The current method of relying on tribunal-generated administrative allocations angers all and satisfies none. Yet it continues, and there is no alternative mechanism for the states to compensate each other. I want to re-up a solution that a crack team at Takshashila had put together in 2017 for allocating water to states in a dynamic, equitable and efficient manner. The solution relies on incentives and pricing to tackle this wicked problem. The logic is as follows:

This set of slides has various scenarios, applying this principle to the situation at hand.

Do check the slides, and tell us what you think. Global Policy Watch: It Is Easy To Lose Yourself In ChinaGlobal policy issues relevant to India— RSJLook, I know China is a large country. How large? Well, people lose their way there often. And they soon disappear. Like they say - bade bade deshon mein aisi chhoti chhoti baatein hoti rahti hai (a whole host of trivial things keep happening in large, important countries) So people disappear. Not just ordinary people. See for yourself. China’s foreign minister, Qin Gang, was last seen in public in June of this year. He then developed ‘health issues’ and was replaced from his cabinet post. No one has seen him since. For over a month now, no one has seen China’s defence minister, Li Shangfu, too. He cancelled his trip to Vietnam scheduled in the first week of September, citing ‘health reasons’. Being a cabinet minister in China does take a toll on your health. Not just ministers, we also have the case of the leader of the Rocket Force, Li Yuchao, and the air force general of the southern theatre command, Xu Zhongbo, being replaced abruptly. Neither of them has been seen in public since. And it has been more than six months now since anyone has seen star banker and dealmaker Bao Fan. Of course, we haven’t really seen Jack Ma, founder of Alibaba, for a long time now. There’s no Google Maps in China. Most of these people possibly used the unreliable Baidu maps and lost their way. That seems to be the most likely explanation. Though I always thought: like in ancient Rome, all roads in China eventually lead to Xi. But what do I know? PolicyWTF: Solving Scarcity by Creating More of ItThis section looks at egregious public policies. Policies that make you go: WTF, Did that really happen?— Pranay Kotasthane In edition #159, we discussed the medical education policyWTF in detail. In short, regulatory constraints have forced India’s medical college intakes to be exceedingly small. While India has the largest medical colleges in the world, it produces less than a third of the MBBS doctors that China produces every year. How do you solve this problem? By reducing restrictions that prevent colleges from scaling up. Naah. Not if you are the National Medical Commission (NMC), which instead plans to stop new colleges from coming up to prevent the unemployment of doctors! Apparently, the venerable NMC wants to cap the number of MBBS seats in existing government and private medical colleges and introduce the ratio of 100 MBBS seats per l0 lakh population in the states. This is a classic case of chasing an imagined idea of equality before achieving sufficient quantity. Why should a state not be allowed to excel in providing medical education? Why should the number of seats be spread equally across states? Why not let the market operate? This move comes merely a few months after the PM spoke about the need for private players to establish medical colleges in the backdrop of Indian medical students being stuck in Ukraine. The NMC’s 1950s style, centrally-planned MBBS seat distribution, though, seems to go in the opposite direction. P.S.: The entire guidelines document is a work of art. Do read the guidelines, which include stuff like yoga training, minimum floor area of dissection halls, and other such specifics. These significant entry barriers ensure that you can’t run medical colleges without political clout to game the regulations. Then we rue why politicians run medical colleges! HomeWorkReading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

If you liked this post from Anticipating The Unintended, please spread the word. :) Our top 5 editions thus far: |