If you go to Canvey Island and park by the little café that sells you terrible grey soft serve ice cream that you put in the bin because it is that bad, then you can walk up on the sea wall around the edge of a vast landscape of storage tanks for gas and oil. One is run by a company called Oikos, they store oil unloaded from tankers arriving into the jetties that stretch out from the sea wall. During the BSE crisis in the nineties they also stored tallow recovered from culled and incinerated cattle. The other one is run by Calor – this is the remnant of the British Gas Council’s late fifties project to bring liquefied natural gas into the country by sea. It was also the starting point of the national grid and the gradual transition from coal and gas derived ‘town gas’ to natural gas. Canvey Island is the birth place of natural gas in Britain, some people would also consider it the birth place of punk music. In his lyrics Lee Brilleaux turns Canvey Island into New Orleans:

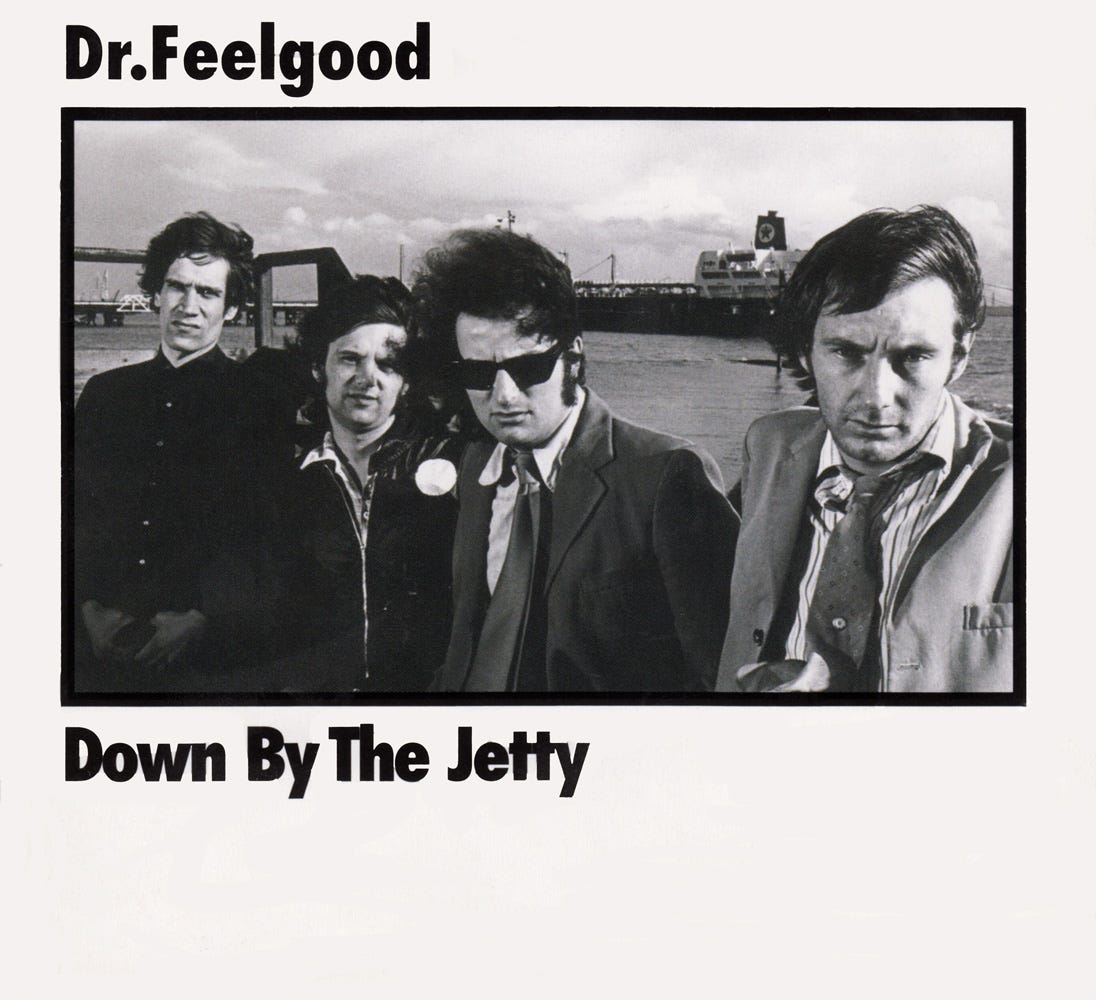

Wilko Johnson’s plays the guitar like a ship engine. It just keeps turning over with this jagged rhythm alongside finger picked riffs, he strums with his fingers so he can shift between rhythm and melody. He walks up and down while Brilleaux stares straight ahead undoing his tie, loosening his collar – his shirt matches his tie. BRICK BRICK DU DU DU LU / BRICK BRICK DUH DUD DUH LUH. Dr. Feelgood live in 1975 [Youtube] In a pub inside the Canvey Island sea wall, they are dressed for a city even though the pub was made for fishermen. They have transformed their estuary hinterland into the Louisiana delta. “Come on Wilko, lets go down by the Jetty” Brilleaux says in a low voice guiding Johnson into an angular solo without ever giving up the rhythm.

Johnson sings a harmony and the white suited drummer keeps going and going – he is known by the moniker: The Big Figure. The Song is called All Through the City, from their Album Down By the Jetty, the band are called Dr Feelgood, its 1975 and their first album has just been released.

Dr Feelgood made music in the shadow of fossil fuels, the towers in the first verse are the flares of an oil refinery, the Coryton and Shell refineries on the other side of Holehaven creek on a peninsula separating Canvey from the Thames Estuary. Behind the Canvey Island sea wall were a number of large storage facilities. Walking around the sea wall now you can see dozens of huge tanks storing gas and oil unloaded from tankers coming into long jetties. In the early 70s while the band began to make music plans were being developed for two large oil refineries to be be built alongside the existing ones. There was a fierce resistance over several years and in 1979 Occidental refineries pulled out, the campaigners claim this as their victory [Link] but in 1978 the project had been declared safe by the government provided certain conditions were met [Link]. Occidental refineries claimed it pulled out for commercial reasons which could have been a consequence of these additional requirements, but it could also have been a result of the turbulent state of energy markets in the 1970s. The Canvey Island report was to become a model for future similar health and safety inquiries. * Dr Feelgood’s enthusiasm for the Mississippi Delta is not the only connection between Canvey Island and Louisiana. In 1959, when Brilleaux was 7 and Wilko Johnson was 12, the first cargo of liquid natural gas was delivered to a new gas terminal built by the Gas Council. The ship had been developed in a partnership with the American oil company CONOCO and the Chicago union stock yards. The ships were designed to store the gas at the -160 C temperatures required to liquefy it and reduce to 1/600th of its volume, kept cool by insulation for the transatlantic passage. Once the technology was established and a new ship was constructed, The Methane Pioneer, the trade shifted so that the gas came from Algeria, but it was still headed for Canvey. Canvey Island where you couldn’t shake the sight of oil and gas containers, refineries and flares, ‘Towers burning at the break of day’. In Louisiana the chemical plants and oil refineries kept being built throughout the seventies and eighties and still keep going up now. 25% of U.S. petrochemical production takes place in the Mississippi delta and its neighbouring river parishes, like Lake Charles and the Calcasieu river where the original Methane Pioneer shipment had started out on its journey to Canvey Island. Plants are particularly concentrated along the Mississippi between New Orleans and Baton Rouge [Link to Propublica story]. Here the incidence of cancer is so high that the area has gained the moniker Cancer Alley. Overall there is a roughly 50% greater chance of developing cancer than elsewhere in the country, but in some areas this chance is much greater than that due to the toxicity [Propublica maps] of the hydrocarbon industries that dominate the landscape. Where toxicity is most concentrated are also the areas with the greatest black populations. This is racial capitalism. Local government have worked with wealthier white populations to protect their areas from pollution whilst black populations have consistently been burdened with the vast toxicity of capitalism’s lifeblood – petrochemicals. Cedric Robinson’s concept of racial capitalism holds that capital depends on the racialisation of groups of people to generate surplus populations who through their labour and their suffering absorb the ‘necessary’ costs of capital so that other populations can profit and thrive. Geographer Thom Davies [Link] has written about what has happened to black populations in Louisiana in terms of racial capitalism and low violence, bodily suffering which is best viewed over decades, but is as cruel and intentional as any other form of violence against a population. Simply put – the black population of Louisiana’s lives are not valued as highly as others in the state and the country at large. In the Mississippi delta right now there are people dying of cancer so that you can benefit from the petrochemicals that are produced by them, and in the places where they live. * Wilko Johnson and Lee Brilleaux were two of the many young British men in the 1960s and 70s who were listening to blues music from Louisiana. People like Muddy Waters, and later Bo Diddley. The trotting rhythm and edgy guitar sound cut through by twanging finger picking and harmonica howls. Vocally too there is an edge and playfulness to the sound — when Muddy Waters sings ‘I just can’t keep for crying’ he stretches the vowels and compresses the consonants, just like Brilleaux tries to do. Compared to some of the other, often more middle class jazzers and rhythm and blues musicians Dr Feelgood have a jagged sound that prefigures punk music. Muddy Waters sings:

Bo Diddley ’s rhythmical and angular guitar sound was one of Wilko Johnson’s inspirations. Maybe his songs most of all sound like what Dr Feelgood were doing. His rattlesnake chorus and sidewinding verse – the story telling and the chick chugging guitar. This is surely what Brilleaux and Johnson were listening to when they were hanging out as young men in Canvey Island:

These are lyrics about living in a hostile place and surviving, about hardening yourself to the conditions, turning snakes into accessories and human skulls into chimneys but still finding pleasure in love, in taking a walk with Arlene. Who do you love? My dad was young and living in Essex in the 70s, I must remember to ask him if he ever saw Dr Feelgood play. He told me that in his early teens – he bought a Led Zeppelin record and he would listen to it in his bedroom with the lights off just staring at the red light on his turntable as Plant howled with the sound of being swept along by Page’s guitar. I imagine Brilleaux and Johnson doing the same when they first got hold of a Bo Diddley record, listening to songs from ten years ago on the other side of the ocean. Hearing songs of love and desire played out on in the places where they lived because they weren’t wanted anywhere else. I don’t want to draw a false equivalence, but maybe something about the dull edge-lands of suburbs and industrial coastal towns made my dad and the members of Dr Feelgood reach out for something in the indicator light of their record players. I’m listening to a compilation of Delta Blues put together by Wilko Johnson and every song demands your attention. What did he find in that sound that spoke to him in his Canvey Island home. Living in a town where the population were being allowed to be surrounded by more and more oil and gas, where no one thought about the toxic symphonies being piped from the Shell Oil refinery, and wanted to build more and more and more. I think these young men found in that sound a sound of marginal life, of singing and playing against the conditions – and living still in spite of them. Of turning a rattlesnake into a necktie. And I guess by the time it got to my dad it sounded like an explosive recognition of everything you didn’t know you were feeling. * Circle back to racial capitalism. Brilleaux, Johnson, The Big Figure, and John Sparks were all white. Like many British bands from the 1950s onwards they were playing music that they had first heard played by black musicians. Whilst their class, and maybe the place they grew up may have worked against them they did not face the inescapable racialisation that intensified the burden of being black in Louisiana in the mid twentieth century six hundred fold. When Brilleaux transformed canvey into the Essex delta it was a kind of act of transatlantic solidarity. Consciously or not he saw that the gas that flared above the refineries, and the turning engine of the Methane Pioneer were a connection with the river landscapes and marginalised populations that would become known as cancer alley. Blues and gas, rhythm and oil. The petrochemical industries do not seem to have inflicted the same burden of cancer on the population in the area as in Louisiana. Brilleaux died from lymphoma aged 41 at his home in Leigh-on-Sea and Johnson survived Pancreatic cancer that was diagnosed in 2012 but I’m not sure their illness can be attributed to oil and gas. An Essex county council report in 2009 found that cancer rates in the Canvey area were in line with the national average. That said, the two areas with higher incidences were also the most deprived areas, and while the report suggests that this is a common correlation it does not preclude the possibility that having to live in an area of toxicity might also correlate with economic deprivation. Maybe the fact that the Occidental refinery was not completed in the seventies also helped combat this slow violence though whether this was a consequence of health and safety regulations or market conditions is unclear. Perhaps it was simply the case that there were more marginalised and racialised populations in the world who could not put up the same resistance to the toxic pollution of the places where they lived. A few years ago at Christmastime Rebecca’s parents arranged for us all to go and see Dr Feelgood play in Ipswich in a venue at the back of a pub. The band no longer have any of their original members, and they have not done so for some time. They were at their best and most successful with Wilko Johnson before he left to play with the Blockheads. There was a fan there for the guitarist, not because of Feelgood, but because he’d played in Eddie and the Hot Rods. The sound had none of the staccato edge of the original line up and the singer none of the charm. But the songs drove on and on. The audience were made up of people the age of my parents generation plus a few people my age who had been brought along, presumably to learn about what real music was. What a strange thing that music can travel so far and through so many people, that Louisiana blues was listened to in Canvey bedrooms, and that the songs keep moving, stiff legs jerking along to Roxette as if it were 1975 and the middle of the oil crisis. Heads bopping just as if they knew they were going to the gas showroom the next day to pick out a back boiler and radiators to be paid for by a local government improvement grant. Though Dr Feelgood have proven to be a renewable resource whereas this is not the case for gas. Like the distance between Son House in Lyon, Mississippi and Dr Feelgood in an Ipswich pub, gas can go far too. Gas is a fuel that links our boiling eggs into a global network of exploitation and pollution. And even if you aren’t getting cancer from it in Canvey or Ipswich, you can be sure that someone somewhere is paying the price for your convenience. The new Truss government’s recently announced and wildly expensive ‘solution’ to the gas price crisis was not just a response to the very real threat to life that this crisis has created, but also a means to try to stop an existential crisis for capitalism. This is partly why Truss has decided to ask energy companies to pay none of these costs, and also to remove a green energy levy and at the same time remove the moratorium on fracking. The government is stepping in more to preserve the life of the fossil fuel energy as they are to preserve the life of the people that rely on this fuel. These companies could have been brought under national ownership, or they could have been forced to spend their profits on a transition to renewable energy, or the government could have spent £150billion + on insulating homes and investing in renewable energy sources. But all of this would mean to acknowledge that there is something wrong on a deeper level, it would be to hear the echoes of slow violence in your favourite seventies pub rock band or your frying pan, it would be to understand that something you have trusted as convenient is actually unjust, and that injustice spreads across, and beneath the earth. It would be to see that fossils can be air, all that is holy is profaned, and to be compelled to face with sober senses the real conditions of life. If you liked this post from Living with Gas, why not share it? |