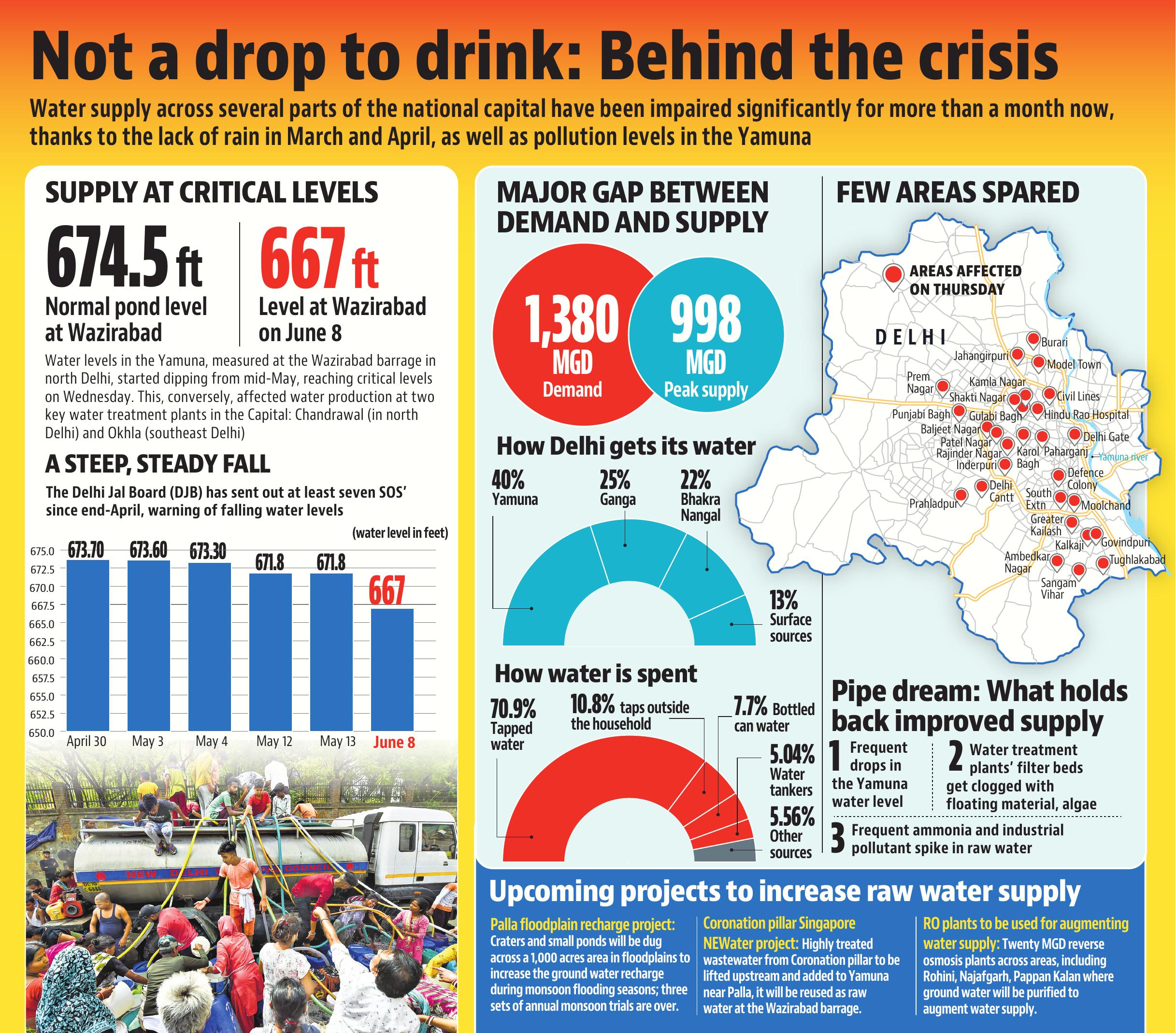

| The crime, the Covid, the politics and the potholes: Capital Letters — Keeping track of Delhi's week, one beat at a time, through the eyes and words of HT's My Delhi section, with all the perspective, context and analysis you need. Good morning! Predictability and Delhi walk into a bar. They don't bump into each other. How I wish they had. Three editions ago, we spoke about scorching heat across the city, with temperatures hitting records in the northwestern and western fringes of Delhi. Then, strong bouts of rain and destructive storms dominated consecutive newsletters (civic staff are still clearing trees that fell prey to the winds two Mondays ago from streets around India Gate). So now, as per the natural progression of things, we'll talk about a severe water crisis that has afflicted most parts of Delhi for the past week. With unforgiving temperatures, and a general shortage of rain, the section of river Yamuna that runs through Delhi is nearly dry. How dry, you ask? Well, officials on Saturday said the water in the river is just six inches high (as tall as one of those small plastic rulers) at the Wazirabad barrage, which is used as a marker to understand the Yamuna's levels.  (A nearly dry Yamuna passing through Delhi. Credit: ANI) According to the state government's 2021-22 economic survey, Delhi needs roughly 1,380 million gallons (5,223 million litres) of water every day, a unit known as MGD. But, on a regular day, when supply and raw water levels are normal, it produces just around 998MGD. This means that even without any excess scarcity, Delhi gets 380MGD lesser water than it needs. But the dry Yamuna means that this gap has widened by another 100MGD or so, leaving most of Delhi with patchy (and dirty) supply. Water from Haryana, via Yamuna and two canals, makes up almost 40% of the raw water entering the Capital. A quarter comes from Uttar Pradesh through the upper Ganga canal, 22% from Bhakra Nangal in Punjab, and the rest is from subsurface sources (like tubewells). Only East Delhi, which is supplied by the upper Ganga canal, seems to have been spared the summer trauma. Residents, meanwhile, were sent on a mad rush for water. Anil Pershad, a resident of Chandni Chowk's Chunamal Haveli, said they had no water for a week. "The mornings are harrowing. We wake up early to arrange a few buckets of water. The helplines don't respond and we are forced to purchase canned water for meeting drinking water demand." The situation was only marginally better in south Delhi's Defence Colony. Maj (retd) Ranjit Singh, who heads Defence Colony Welfare Association, said that parts of the area are either getting very little water or that the supplied water is smelly or dirty. "This situation has prevailed for the last 10 days. Many pockets of the colony are affected," he added.  (Click to expand) Political leaders waded into the crisis. The Delhi government blamed Haryana for the shortage, alleging the neighbouring state was withholding water. Chief minister Arvind Kejriwal requested his Haryana counterpart Manohar Lal Khattar to release more water on "humanitarian grounds". Then, on Saturday, the state government asked Haryana to release water from the Somb, a tributary of the Yamuna, arguing that the river "was full of water". Khattar countered that his state did not have excess supply to distribute if Delhi "uses its fixed quota". Regular supply hiccups are a summer feature for water-stressed Delhi, especially since it is largely dependent on channels beyond its borders. A dry Yamuna kicked up a major firestorm in July last year as well, with the Delhi water utility taking the issue to the Supreme Court (which dismissed the plea). Another shortage hit the city in February that year, thanks to repairs in the Nangal hydel channel. These recurrences have increased Delhi's reliance on groundwater, which itself has kicked up a whole bunch of problems, causing some parts of the city to literally sink beneath our feet. The climate crisis means that such problems will only become routine and more acute. So, as an HT editorial in January said: "Delhi has the potential to harvest 12,800 million litres of rainwater every year. The government and citizens must treat groundwater as a valuable resource and its rapid depletion as an emergency, which can threaten economic growth and reduce the quality of life for citizens…" |