While excellent newsletters on specific themes within public policy already exist, this thought letter is about frameworks, mental models, and key ideas that will hopefully help you think about any public policy problem in imaginative ways. Audio narration by Ad-Auris. If this post was forwarded to you and you liked it, consider subscribing. It’s free.

PolicyWTF: Revdi Fertiliser CultureThis section looks at egregious public policies. Policies that make you go: WTF, Did that really happen?- Pranay Kotasthane In the past, we have discussed many government plans of the “One Nation, One X” kind. Still, I must confess. Of all things that can substitute the letter X, “fertiliser” was beyond my thinking horizon. Limited thinking wasn’t a problem for the government, which has:

While you decipher what this order means, a short detour about the abbreviation PMBJP is in order. Its usage suggests something profound — the government is finally running out of acronyms! I claim so because there’s an existing scheme with the same abbreviation in the very same ministry — the older Pradhan Mantri Bhartiya Janaushadhi Pariyojana (PMBJP), run by the Department of Pharmaceuticals since 2008. Perhaps the reason for repeating this abbreviation is apparent — it comprises both the ruling party and the party leader. To make matters more confusing, this scheme has been hailed as “the call of #NewIndia which will take our nation to greater heights” by a politician whose name also abbreviates to BJP. The new PMBJP seems utterly bizarre at first. Why would the government want all companies—government-run or private—to sell their products under a single brand name of ‘Bharat’? Why would a government order go to such lengths to specify that “Two-thirds of the area on the top half of a fertiliser bag will be used for the official branding and logo of the PMBJP while a fertiliser firm can use the rest one-third area for its own logo and branding as well as printing other information relating to the product”? If you dig deeper, the bizarreness gets replaced by a sense of rejection. The diktat to dissolve the value of all fertiliser brands only takes the veneer off the sham called a market for fertilisers. Here’s how. The fertiliser sector is insanely regulated even by Indian standards. It all began with good intentions. One of the components of the Green Revolution was to subsidise agricultural inputs. And so, a fertiliser subsidy was introduced. The government fixed the retail price of urea fertiliser considerably below the market price to encourage its usage. This difference between the market and administered prices was called “fertiliser subsidy”. The government paid off the difference to fertiliser companies with taxpayers’ money. Simultaneously, the government started running fertiliser plants to increase supply. Combined with the Minimum Support Price (MSP) mechanism guaranteeing procurement of certain grains, these measures worked to the extent that Punjab, Haryana, and a handful of other states were able to increase grain production rapidly. The fears of India’s dangerous “population bomb” subsided. But as you might anticipate, interfering with prices had unintended consequences. An overuse of subsidised fertilisers led to a decline in soil quality. An artificially low price also led to the diversion of urea for non-agricultural uses. Urea is a versatile material used in textiles, paint, explosives, and medicinal sectors. Naturally, people purchased cheap fertilisers from retail shops and diverted them to these industries. The government then introduced the Fertiliser (Movement Control) Order, 1973. Fertiliser couldn’t be sold across states within India without the ministry's permission. Instead, state-level fertiliser requirements were aggregated at the union ministry level, and each state had its quota “allocated” from in-state and select out-of-state fertiliser manufacturing facilities. And, of course, there were the usual export restrictions until recently. Essentially, there’s no such thing as a market for fertilisers. Just as MSP effectively turned farmers into government employees, the fertiliser subsidy turned manufacturers into satellite government agencies meant for supplying fertilisers. Meanwhile, the fertiliser subsidy bill kept rising. It is now the union government’s second-largest explicit subsidy, behind only food. For reference, India spent more on fertiliser subsidy last year than it did on defence capital expenditure. This year, higher international prices due to the Ukraine war mean that the government’s fertiliser subsidy bill will shoot up further. And so, the government decided: if we’re going to pay Rs 2 lakh crore to our fertiliser contractors (companies) annually, why not claim the full credit for it? And that’s how we got the One Nation, One Fertiliser scheme. While the name might seem bizarre, it is just the high point of continued government interference in this sector. We can anticipate the unintended consequences. Fertiliser companies—now unable to differentiate their products—will be further disincentivised from improving or innovating. With the PMBJP branding at the front and centre of every fertiliser bag, the endowment effect of the subsidy will grow stronger. It’s now explicit that the government supplies fertilisers to farmers, not companies. Which government will now take the risk of being seen as anti-farmer by reducing this subsidy bill? A better alternative would’ve been to eliminate all complex controls over the fertiliser sector and increase the amount provided as income support to farmers under the PM-KISAN scheme instead. A subsidy to fertiliser manufacturers made sense in the 1960s due to food shortage. It continued to make some sense until there was no way to identify farmers. But now, with an income support scheme already identifying farmers via Aadhaar, it is unconscionable to direct taxpayer money for another subsidy programme. We are stuck in a low-level equilibrium that just keeps getting worse. Global Policy Watch #1: Karza Maaf KaroGlobal issues and their implications for India— RSJ The wonderful thing about bad ideas is how so many politicians find them good. Good ideas must go through the steeplechase of policy proposals, committees and reports. Then they run the marathon to solicit bipartisan political support and public acceptance. And, if they are lucky, they make the finish line alive. No such test of endurance for bad ideas. They fly past these hurdles flipping the bird to them. Time and place don’t matter. Bad ideas are welcome. Everything, everywhere, all at once. The immediate cause for that short ode to bad ideas is the announcement by the Biden administration this week of a student loan forgiveness programme. If you missed the news, here’s a summary from New York Times:

Good IntentionsWhat will this cost the exchequer? There is a wonderful report on this by the Penn Wharton Budget Model team at the University of Pennsylvania. It has a detailed analysis of the impact of the announcement. I will leave you with the summary:

All right. $605 billion under static assumptions and $1 trillion based on future behaviour changes. I will bet this will easily go north of that number because such announcements change the credit culture of a society. We, Indians, know it. So, apart from the $1.9 trillion that Biden announced early last year as part of the COVID-19 relief and build back better package, we have another trillion of stimulus being given back to largely the top two quintiles of the US households. A trillion here, a trillion there, and pretty soon we are talking about real money, to misquote that famous quip by Senator Dirksen. Of course, there are these pious reasons for this policy from the White House press release:

A college education is a passport to higher income and better life in the US. It is the single most significant determinant of social mobility. Two data points from this Pew report puts this in context. First, in 2021, full-time workers ages 22 to 27 who held a bachelor’s degree, but no further education, made a median annual wage of $52,000, compared with $30,000 for full-time workers of the same age with a high school diploma and no degree. Second, households headed by a first-generation college graduate – that is, someone who has completed at least a bachelor’s degree but does not have a parent with a college degree – had a median annual income of $99,600 in 2019, compared with $135,800 for households headed by those with at least one parent who graduated from college. The median wealth of households headed by first-generation college graduates ($152,000) also trailed that of households headed by someone with a parent who graduated from college ($244,500). A college education helps you earn more. And if you have two generations of college education in your family, you’re made. This should be a sufficient incentive for people to take the risk of a college loan and graduate because it does make a difference. Also, the so-called debt burden as a percentage of income is disproportionately high among people who take student loans but don’t graduate. About 40 per cent of students who take loans never graduate. They find it difficult to shrug off the burden throughout their lives. Unintended ConsequencesWhen you look at the data together, you should reach the following conclusions:

The debt forgiveness program of the Biden administration doesn’t solve the fundamental issue of high college fees. Neither does it strengthen the alignment of incentives between the lender and borrower. In fact, an announcement like this will possibly spur more college applications in future in anticipation of future relief packages like this. That will raise the demand for college seats and increase tuition fees further. Worse, as many have already pointed out, such relief packages have a moral hazard built in. We have written about this in the context of farm loan waivers in India. There are two problems here. When you waive the loans, what do you tell those repaying their debts regularly at great costs to themselves? That they were stupid to do so? Secondly, you have set a precedent for future packages like this. Once that mindset sets in, more borrowers will be taking loans and defaulting because they know the government will bail them out. Mihir Sharma has drawn exactly this parallel with the Indian case in his Bloomberg column this week. He writes:

The other problem is inflation. The consequences of mindless packages since the beginning of the pandemic are there for all to see. The US inflation is at a 40-year high. This relief package will put more money in the hands of the middle class that is already using its excess savings built up during the pandemic to drive up prices. The Fed has been pushing up interest rates to tame inflation. There’s a serious possibility of a recession and debt defaults among the most vulnerable borrowers because of rising rates. More importantly, if the market starts believing that the government doesn’t care about inflation, then high inflation expectations will lead to a real increase in prices. Inflation is expectation driven. It is a self-fulfilling prophecy. That’s why the Fed is careful about its words and why analysts spend so much time parsing its statement. Who in their right mind would want to do this now and set such expectations? The inflation point is particularly important to the rest of the world and to India. Otherwise, who cares what student loan policies are pursued by the Biden administration? Unfortunately, US inflation, interest rates and growth matter to us, as we have already seen in the past few quarters. This bonfire of good economic thinking will singe us. But the persistence and universality of bad ideas cannot be easily fought. There are always short-term reasons to contend with and, of course, elections to be won. Biden’s move is to shore up his popularity among the youth and possibly give Democrats a fighting chance in the mid-terms. These don’t turn out well. But who cares about the future? India Policy Watch: The Elements of Revdi CultureInsights on burning policy issues in India— Pranay Kotasthane The PM’s revdi culture remark castigating state governments for distributing freebies has been widely debated over the last month. Everyone and their uncles have dipped their toes in the discourse stream. Those on the left have tried hard to prove that freebies are, in fact, desirable social sector spending. Those aligned with the government have highlighted the fiscal imprudence of state governments handing out laptops, TVs, and mixer grinders before elections. My only advice is to read more public finance specialists on this issue and fewer political scientists. What classifies as a subsidy or freebie? Which level of government is guilty of doling out freebies indiscriminately? The discipline of public finance has a lot to offer on such questions. The landmark paper on subsidies in India is by M Govinda Rao and Sudipto Mundle in 1991, in which they devised a subsidy classification. They neatly define a subsidy as:

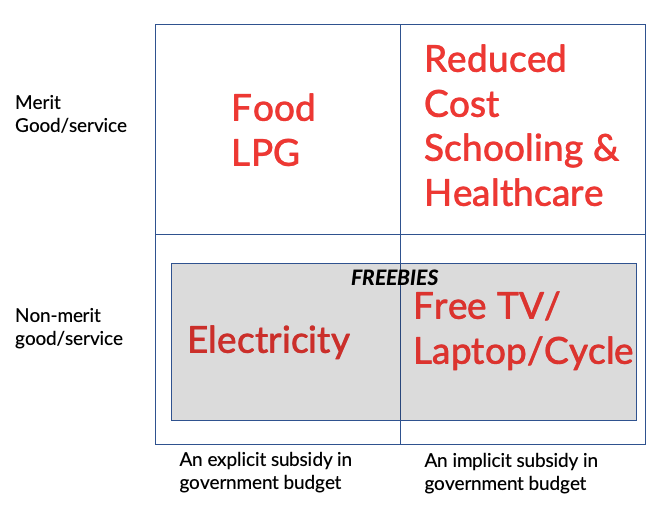

Based on this broad definition, we can classify subsidies along two axes: the nature of the good or service subsidised (merit vs non-merit) and whether they are recognised as subsidies in government accounts (implicit vs explicit). The chart below is my representation of subsidies at the intersection of these two axes. Of the four categories of subsidies, we can now define freebies as non-merit goods which are explicitly or implicitly subsidised by the government. The bone of contention here is the “meritorious” nature of goods. The above paper takes a liberal approach and classifies any good with positive benefits to people beyond the recipient as a merit good. This classification now allows us to understand freebies' volume and nature better. The 1991 paper found that Indian governments were collectively spending almost 15 per cent of GDP on subsidies. Continuing this line of inquiry, Mundle and Sikdar find that the total volume of subsidies had fallen to 10 per cent of GDP by 2015-16. The union government only accounted for 30 per cent of this subsidy bill. State governments accounted for the remaining ~7 per cent of GDP spent on subsidies. Crucially, states subsidised both merit and non-merit goods/services. Since social services like health and education are the primary domain of states according to the constitution, they end up spending ~3 per cent of GDP on such merit goods. The remaining 4 per cent of GDP was spent on non-merit goods. So, the PM’s statement is not incorrect. Both state and union governments have to set their house in order, but on freebies, the state governments have a lot more work to do. The punchline from Sudipto Mundle’s article in Indian Express is vital gyaan for anyone working in Indian public policy:

Global Policy Watch #2: Falling In Love With “Your” PoliticianGlobal issues and their implications for India— RSJ Taking the cue from the loan forgiveness piece, the question often asked is why do politicians behave the way they do when it is evident that the long-term consequences of their actions will be bad? Like I mentioned a few weeks back, I have been reading an anthology of essays by Bryan Caplan titled - “How Evil Are Politicians?: Essays on Demagoguery”. Caplan introduces the notion of power-hunger in one of the essays and how rational politicians continue to raise it and then try their best to satiate it. Caplan writes:

Then he argues that democracy and its check and balances might blunt this naked pursuit of power, but that is never enough. He writes:

So, what’s the solution? Eternal vigilance. And not to be enamoured by any politician and their promises of making your nation great again or reclaiming your deserved vishwaguru status. That’s easier said than done in these days of tribal loyalties and mass disinformation. Bad policies have a lot going for them. HomeWorkReading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

If you liked this post from Anticipating The Unintended, please spread the word. :) Our top 5 editions thus far: | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||